Interview with Brenda Hartill

Born in London, England, Brenda Hartill emigrated to New Zealand with her parents in the late 1950’s, and was educated there, graduating BA honours at the Elam School of Fine Art Auckland. She returned to London in the 1960’s to study at the Central School, specializing in Theatrical Design. She then worked as a freelance designer in UK theatre, including the West End, and the National Theatre (Young Vic). In the early eighties, she turned towards printmaking and has successfully published her own prints since. She is a member of the Royal Society of Painter Printmakers (RE) and The Rye Society of Artists.

1965 New Zealand Arts Council award to the Central School, London.

1971 UK Arts Council award for young theatre designers, to the Young Vic.

2004 Wrote “Collagraphs and Mixed Media Printmaking”

2012 “A Sculptural approach to Printmaking” an instructional DVD

2001 - 2012 Featured in “Printmaker’s Secrets”, by Tony Dyson, 2009; “Installations and

Experimental Printmaking“ by Alexia Tala, 2009; Intaglio Printmaking by Mychael Barratt

2008; “Printmaking for Beginners”, Jane Stobart 2001.

Exhibitions

Roche Gallery, Rye (2023). New Art Gallery, Eastbourne (2022 Bankside Gallery), major retrospective “TIMELINE”, 2014, New Academy Galleries, Windmill Street, London (11 solo shows 2013 - 1991,) Saffron Gallery, Battle (solo 2015, 2012,), Cambridge Contemporary Art, (solo2016 2011; April 2008) St Georges Chapel, for the Windsor festival(solo 2009), Hastings Arts Forum, (solo 2009), Roche Gallery, Rye (solo 2008), Attic Gallery, Swansea, (solo 2016, 2009, 2007,1997, 1994, 2018); Lane Gallery Auckland, NZ (solo 2007, 2004) Plus many mixed exhibitions.

Artist Statement

Most of my recent works are to do with connecting and developing the ideas I have nurtured over the years. My visual language evolved originally through careful and detailed figurative drawing, which has gradually become freer and more abstract as time moves on. As I head for my 80th year (I’ve just turned 79) I am now enjoying a period reflection and enhancement, and I have a shimmering bank of shapes, forms and textures with which to compile my new paintings, collages and encaustic works. My work is experimental, abstract and embossed. Collagraph, etching, watercolour, acrylic, collage and encaustic works. My main love is abstracting the essence of the landscape in richly coloured textured works, often enhanced with silver and gold leaf. Recent works include a series of watercolour paintings with collagraph embossings, and mixed-media collage/acrylic works. My early experience as a theatrical designer has led to a sculptural approach to painting and printmaking. My work develops though the materials I use and an on-going fascination is with erosion, weather patterns, natural textures, growth formations and universal organic forms. I like to think my collectors can find their own connections to my images, and I don’t like to spell out the imagery too specifically. (finding titles is a nightmare) Most of us can be moved by colours and images in nature: the light on an amazing sky; the sea of blue in a bluebell wood; the patina on a piece of weathered metal or a polished piece of old wood, without needing an explanation as to why they get pleasure from looking at it. I have a great collection of pieces of driftwood I compiled during a visit to New Zealand – they sit in the hand softly and have been shaped by nature. Initially by the growth patterns in trees, then modified by the whirling waves of the sea, the grinding of the sand and tossing of the pebbles. They speak to me and I use the forms in my imagery.

Your work seamlessly integrates various textures and patterns drawn from landscapes, ranging from finely drawn figurative works to bold, heavily embossed abstract images. Could you elaborate on your process of selecting the appropriate medium for a specific piece—be it printmaking, collage, or painting—and describe how the chosen medium influences the overall thematic and aesthetic outcome of your artwork?

I was never interested in reproducing images readily from drawings, and I never used photographs to copy the things I liked about an image. Drawings and photos remind me of the how the image makes me feel and are the starting point to my interpretation. While the early etchings were about Londoners’ London, and were simplified, finely drawn images about living and bringing up children in South London (kites on the heath, children playing in the snow, trains and the urban landscape). As I became more adept at the etching process, I was aware of the three-dimensional possibilities of the medium. This led to my early use of blind embossing (printing without ink, to make indentations in the snow)

Many of the works I produced in my early semi-abstract landscape etchings I developed to push the medium. They were built of a variety of small plates often left in the acid for varying lengths of time and were compiled and switched around as I went along. Some of the images served as a sky in one print and a rock or snow in another. Sometimes I has 30 plates bubbling away at the same time, and I was able to risk ruining the ones I left in for a long time. The acid produced wonderful textures, by a process of erosion, just like nature.

The contrasting lighting conditions of Southern Europe’s strong light and shadow, New Zealand’s remote landscapes, and the greyness of London and Sussex have a profound impact on your art. How do you navigate these diverse environments to shape your artistic vision, and in what ways do these varied light and shadow conditions inform your techniques and color palette in both your figurative and abstract works?

The New Zealand landscape where I lived for 8 years as a teenager in Auckland, instilled an interest in the native bush, and I spent hours drawing the pattern and textures of the trees. Manuka, Pungas, and Puriris, and tangle of bark, vines, and undergrowth of the bush. (I later switched to collecting actual textures, vines and mosses to use directly in my collagraphs).

I had a great geography teacher, Mr Rose, who took us on “tramping” trips in the Waitakare Ranges. Subsequently we had a week tramping beside Ngauruhoe, an active volcano in the centre of the North Island. There I fell in love with Mr Rose, geology, the formation of volcanos, and the power of earthquakes, while also being scared every time there was a rumble in the earth.

Much Later due to my collage friend Prue being married to Sir Tim Wallace (Mr helicopter), I loved seeing the South Island mountains from the air, which eventually led to etching/collagraph images. At this time I realised how much I viewed landscape from above, and hated obvious perspective.

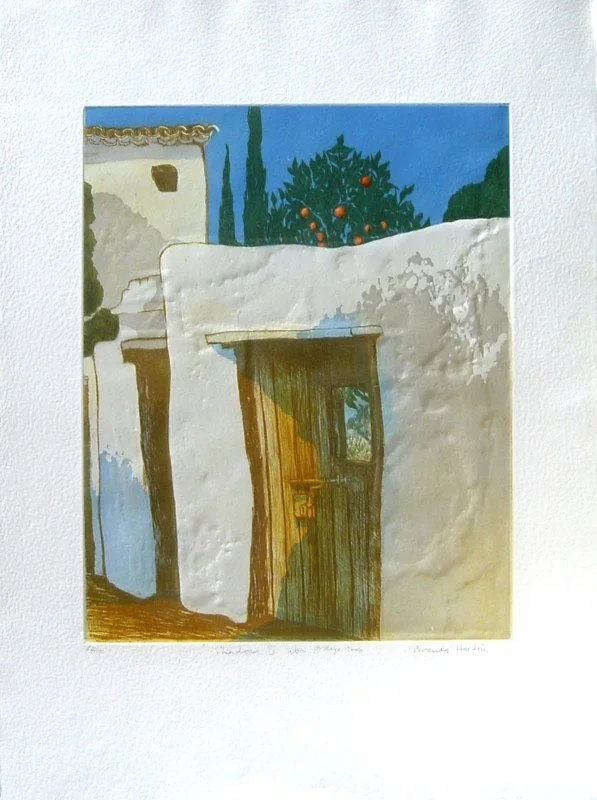

I have always been very aware of strong light and shade, and in the 1980s we bought a house in Gaucin, Andalucía and I set up a studio there. I loved the shadows on the undulating whitewashed walls, so my interest in embossing was employed giving another dimension to etching. I produced a series of 3 plate etchings, using aquatint and printing the embossed plate at the end. The “Shadows” series. Also, at the same time I was aware of the “glimpses” one often sees between houses in a tightly packed village, and so many of my landscapes at the time reflected this, without spelling out the picturesque.

Transitioning from figurative to abstract art marks a significant evolution in an artist’s journey. Can you identify and discuss some of the pivotal moments, influences, or experiences that propelled you towards abstraction? Additionally, how has your conceptualization of landscape imagery evolved throughout this transformative process?

I became aware that some of my early works, coming from a deep sense of family and motherhood, were perhaps a bit sentimental. After a few years of working in my back bedroom in Catford, drying the prints on my bed, I found a warehouse studio overlooking the railway, not far from the river Thames and the mix of warehouses, trains, street markets and stations.

In the 80s I produced a series of “Trainscapes” and “Cityscapes”. The old industrial buildings were beginning to be recognised as good architecture, and now those that are left, command big prices. I was fascinated by the textures and patterns of eroding brick, and many of my works, while based on actual buildings which do not exist now. I did hundreds of drawings wandering around South London, then photocopied these often needing to change the scale to get it right (there were few computers to do the donkey work then). The images were complicated, and produced on strips of metal, receding into the distance. I was moving away from the realistic to a conceptual approach.

Your recent endeavors into embossed watercolor paintings and mixed-media collage paintings have introduced new dimensions to your body of work. What specific challenges have you faced in mastering these new techniques, and what have been some of the most surprising or rewarding discoveries you’ve made in the course of this exploration?

My interest in texture and embossing led me to push the media as hard as possible, and the pressure on the press was pushed to the limit. This led to a whole different way of printing. I started to use materials stuck onto a board base, and later actual plants, which I prepared by pressing and drying out the material. The blankets on my press were tested and for a while I had to use rubber blankets. I had discovered collagraph, a print made from a collage!

I became adept at drying and pressing plant material, to compile images which belied their origin. Thus, weeds became magical forests and ponds, cut card became abstract pattern, string and fibres became water and the sea. I was not interested in making obvious plant and flower motifs, but in how they could be transformed into the universal elements of growth. So many plants and trees echo our own body structure: the maze of nerves and muscles which create a human being.

Now I am using these collagraph and abstract etching works as a basis for collages and paintings. I have enjoyed testing the wonderful range of different art materials now available: silver and gold leaf, guilding wax, acrylic ink, gold and silver pens as well as watercolour, and acrylic paint.

Themes of plant growth dynamics and natural erosion are central to your work, encapsulating the essence of organic processes. How do you approach the abstraction of these complex natural phenomena, and what are the key elements or motifs you aim to highlight to convey a deeper message or evoke specific emotions in your audience?

The amazing range of natural structure and organic growth available mainly in my garden or local beaches and woods lend themselves to the techniques I have developed over the years. My embossed works lend themselves to receiving texture enhancement, and the enriched surfaces can be highlighted, or removed to re-develop the image, helping the viewer to “see the light”

Your early career as a theatrical designer must have provided unique insights into visual storytelling and spatial dynamics. How has this theatrical background influenced your current art practices in printmaking and painting? Are there specific techniques or principles from theatrical design that you consciously incorporate into your artwork, particularly in terms of composition, lighting, and texture?

My years in the theatre, lead me to understand the importance of light. Often I would be on a ladder flinging and spattering a variety of colours onto a surface to enable the lighting designer to pick up and manipulate changes in colour and light during a performance. For a while I worked at the Young Vick Theatre, part of the British National Theatre, and was lucky enough to collaborate with some top-flight sparkies. My simple set for “Rosencranz and Guildenstern are dead” at the Criterian Theatre in London was transformed when it was properly lit. Soon after, when I had babies, I had to give up working as an itinerant designer and learnt printmaking at Morley College because it had a creche. I fell in love with etching!

Years later, when I was producing deeply bitten images, this led to inventing a technique of ink application, I called “the rubs”. This consisted of inking the plate with extended colour, wiping it clean and then rubbing two or three of the primary colours one after another gently on the surface of the plate. This method was particularly successful when my work became highly textured.

The incorporation of rich textures and metallic elements such as silver and gold leaf adds a distinctive layer of complexity to your pieces. Can you delve into your creative process for integrating these materials, discussing both the technical aspects and the conceptual significance they bring to your work? How do these elements enhance the visual and tactile experience of your art?

When I first produced images with silver and gold leaf, I wanted to use the torn edges to add to the dynamics of the piece. I would ink up the plate with “the rubs”, tearing the leaf roughly to add another dimension. Then after I pasted the back of the leaf, with luck it would stick when printed. Now with my unique pieces, I am taking this process a step further, by developing the textures in the prints by hand-colouring and rubbing with various materials. Most recently I am interested in producing delicate pearl-like images, and complex patterns of texture. I also find I can kill the texture when painting with opaque paint, re-inventing the basic shapes, and completely changing the composition.

With a personal history that spans the diverse landscapes and cultural contexts of New Zealand and the UK, how do these varied environments intersect and influence your artistic expression? Are there particular memories, scenes, or cultural elements from these places that have left a lasting imprint on your work, and how do you reconcile or juxtapose these influences in your compositions?

I am currently living in the countryside, in an ancient Oast house near Rye, so the last 20 years I have been living in the countryside with over an acre of land, and great studio. My husband died recently leaving a wonderful garden full of New Zealand and Australian trees. I am now 80 and not able to use my trusty big press now, so collage and re-invention of my huge bank of collage materials suits me well. I have taken up gardening, and have a great assistant Nicola, so I am interacting with the landscape and enjoying planting flowers and vegetables too. New Zealand and Spain are in the past, wonderful experiences but I have moved on. I miss my print-making, and my world is smaller now, but my Art is still of great importance. to me.

As an established artist with a rich and varied portfolio, how do you strike a balance between maintaining your distinctive artistic style and experimenting with new techniques and ideas? What internal or external factors drive your continuous evolution as an artist, and how do you ensure that your work remains both innovative and true to your artistic vision?

I have always been an experimenter and to be honest I can’t work without trying to break new ground. The purist printmakers see me as a bit of a rogue and I break the rules all the time. However, strangely, I have re-printed some of my coloured early works in black and white, which I now prefer! My biggest print, Sheets, an image gathered on holiday in Corfu, of crisp white sheets drying in in an olive grove, was reprinted in black and white recently

Your ongoing fascination with weather patterns, erosion, and natural textures suggests a profound connection with the natural world. How do you stay inspired and attuned to these natural phenomena in your daily life and artistic practice? Moreover, in what ways do you hope your art will inspire others to cultivate a deeper connection with and appreciation for the natural environment?

Luckily my inspiration in the natural world is still as strong. Where I live, I am surrounded with wildlife: birds, rabbits, fish, foxes, and my two beautiful cats. I have a fabulous view from my house, wonderful inspiring plants in my garden: a huge flowering cherry tree, exploding into flower in the spring, a Wollemi Pine, and a Punga tree fern in my garden, along with a cloudscape every morning!