Interview with Jeff Kaufman

What were the biggest challenges you faced when you first started out as an artist in NYC and LA, especially coming from a family with no background in art, theatre, film, or politics?

My biggest challenge was my own ignorance. There was a lot I needed to learn about the world, and about myself. Growing up, I had a passion for politics, art, and classic movies, but I struggled in school and didn’t know what to do with those interests. I think for every artist it’s vital to see a path that connects where you are to where you want to be. That can come from knowing art history (personal stories, not just chronology), exploring the contemporary art world, and being part of a community.

How did your experience at The New Yorker influence your transition into documentary filmmaking, and what drew you to focus on human rights and empowerment themes in your documentaries?

In high school I had a crazy notion of doing cartoons for The New Yorker, so when I dropped out of college, I moved to NYC and somehow got a job in the magazine’s mailroom. That became my real higher education. I met some great writers and artists, went to galleries and museums, and submitted cartoons every week. After countless rejections, I finally sold and had published four or five cartoons to The New Yorker at the age of 21. It didn’t change my life, but it did show me that determination and a flow of new ideas can pay off. I wish I saw within me what art and painting mean to me now, but that needed more time to develop. Most important from that experience was the chance to become friends with legendary film critic Pauline Kael. She lived in Great Barrington, MA and came to NYC every month or so. I was in many ways a rube, but I loved old movies and always arranged to be the person who carried her bags to Grand Central Station. For some reason, she took a liking to me, and eventually invited me to visit her home for a weekend. It was the first time I’d been in a house full of books. Pauline was animated by an enormous curiosity, and she was passionate about many things beyond film.

I think when we open our eyes to other people, we can also start seeing ourselves more clearly.

My concern for human rights came from some of my political heroes like Rep. John Lewis (who I had the pleasure of meeting several times), the humanity you feel reading Van Gogh’s letters, and the inequity that defines so much of this world. For 6 years I hosted / produced a daily 3-hour talk radio show in Vermont and that gave me the opportunity to meet some remarkable people who found purpose in helping others (locally and internationally). After transitioning from radio to television, I wanted to use film to tell those kinds of stories. I eventually formed my own production company (Floating World Pictures, a translation of the Japanese school of printmaking, Ukiyo-e), and made a half-dozen short films for Amnesty International. I’ve directed, produced, and written a wide range of documentaries, and I’ve been really, really lucky to work over the last 10 years with producer Marcia Ross (we’re also married). Our most recent documentary was about Iranian human rights attorney and political prisoner Nasrin Sotoudeh. Knowing people like Nasrin who put their life on the line for democratic freedoms is a continual inspiration.

Can you describe your unique process of applying and scraping down acrylic paint on wood panels hundreds of times? What significance does this method hold for you?

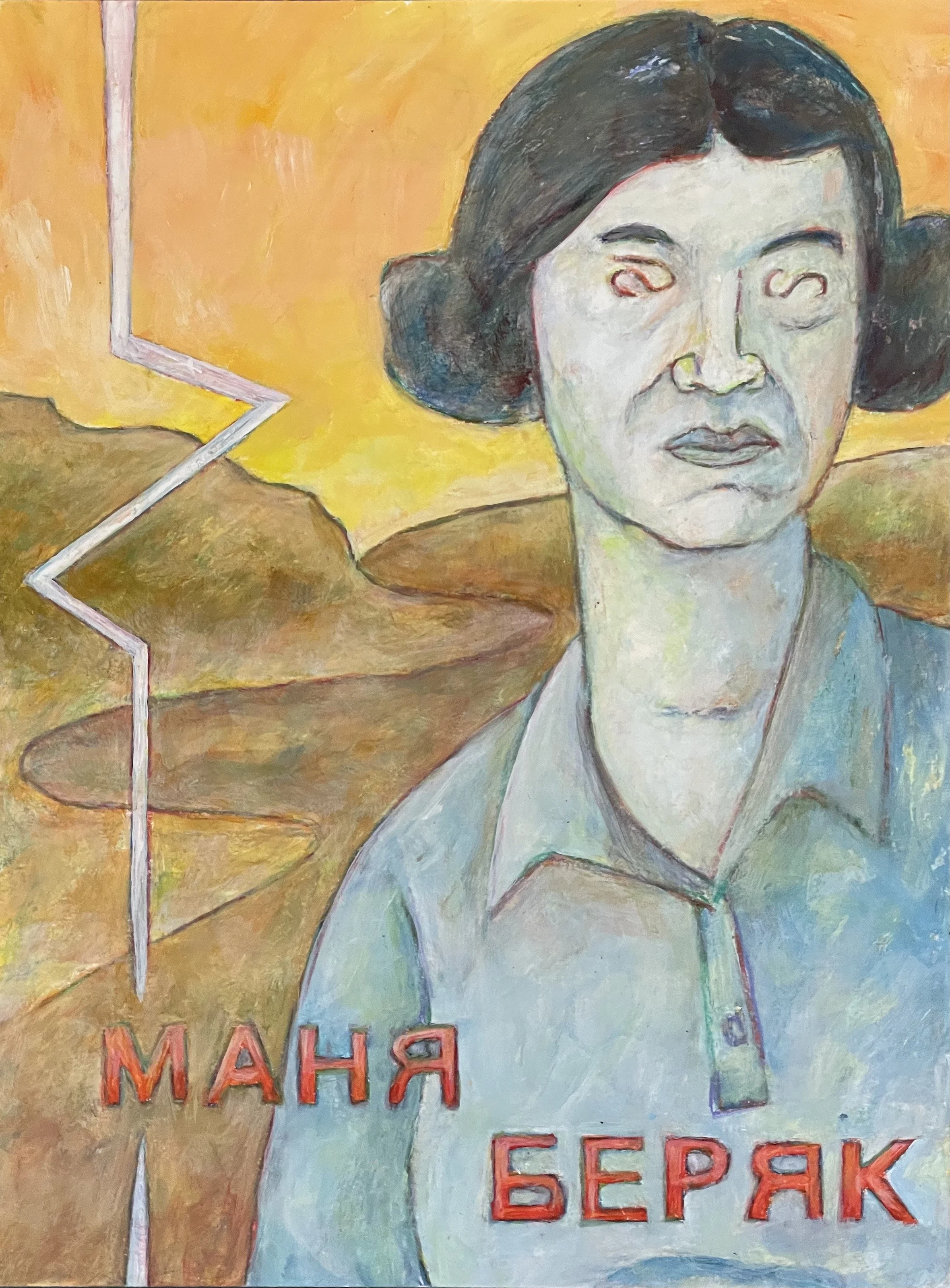

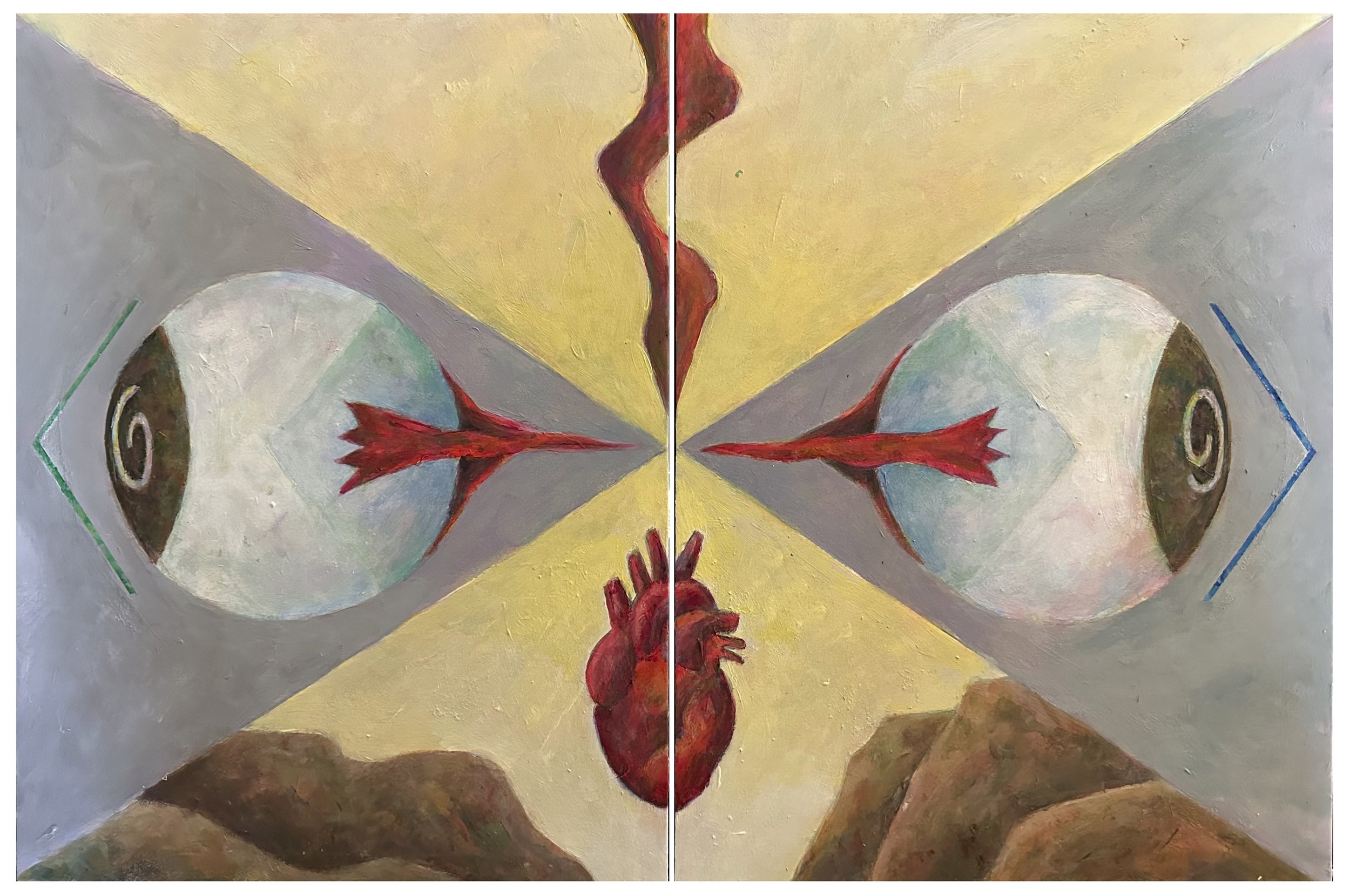

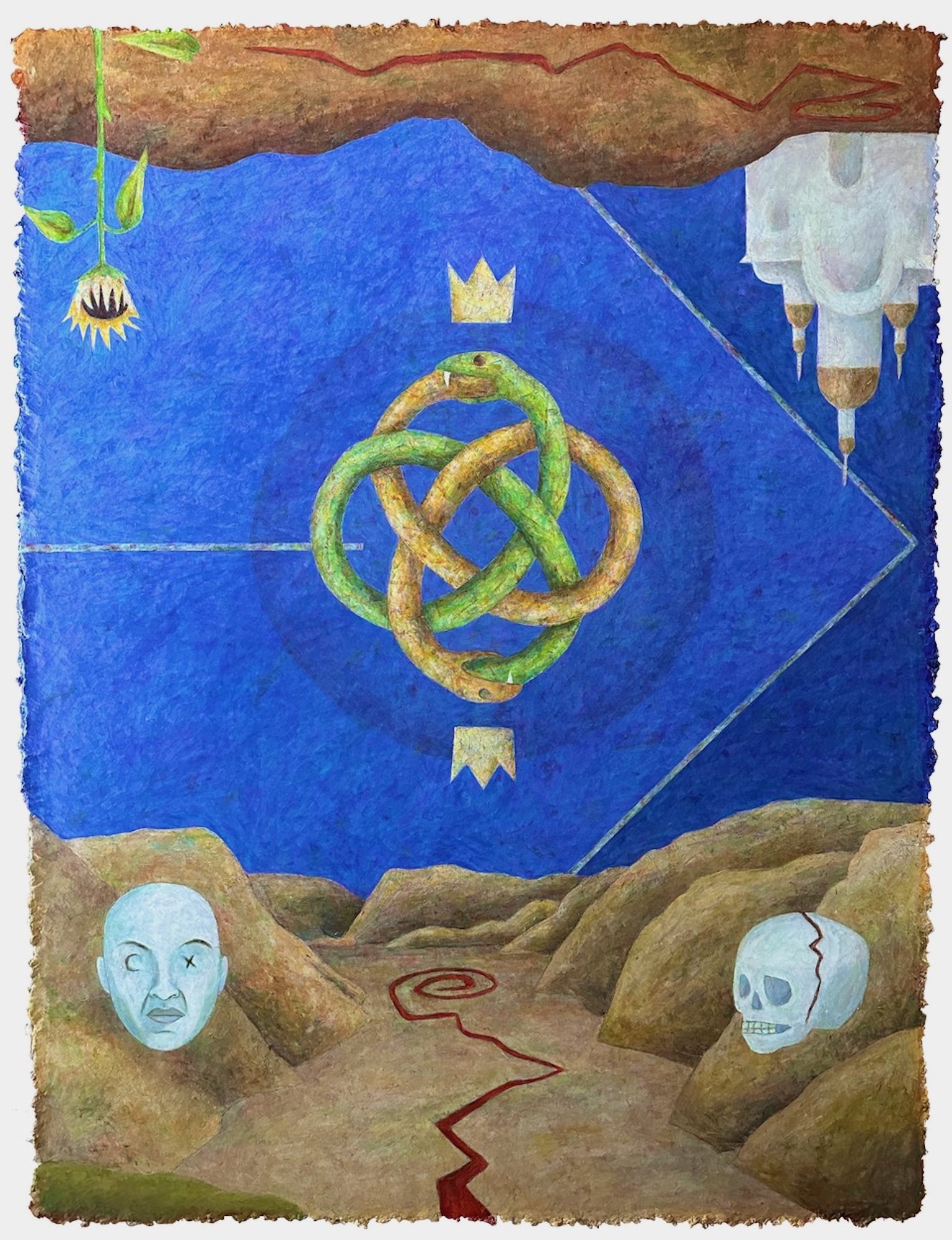

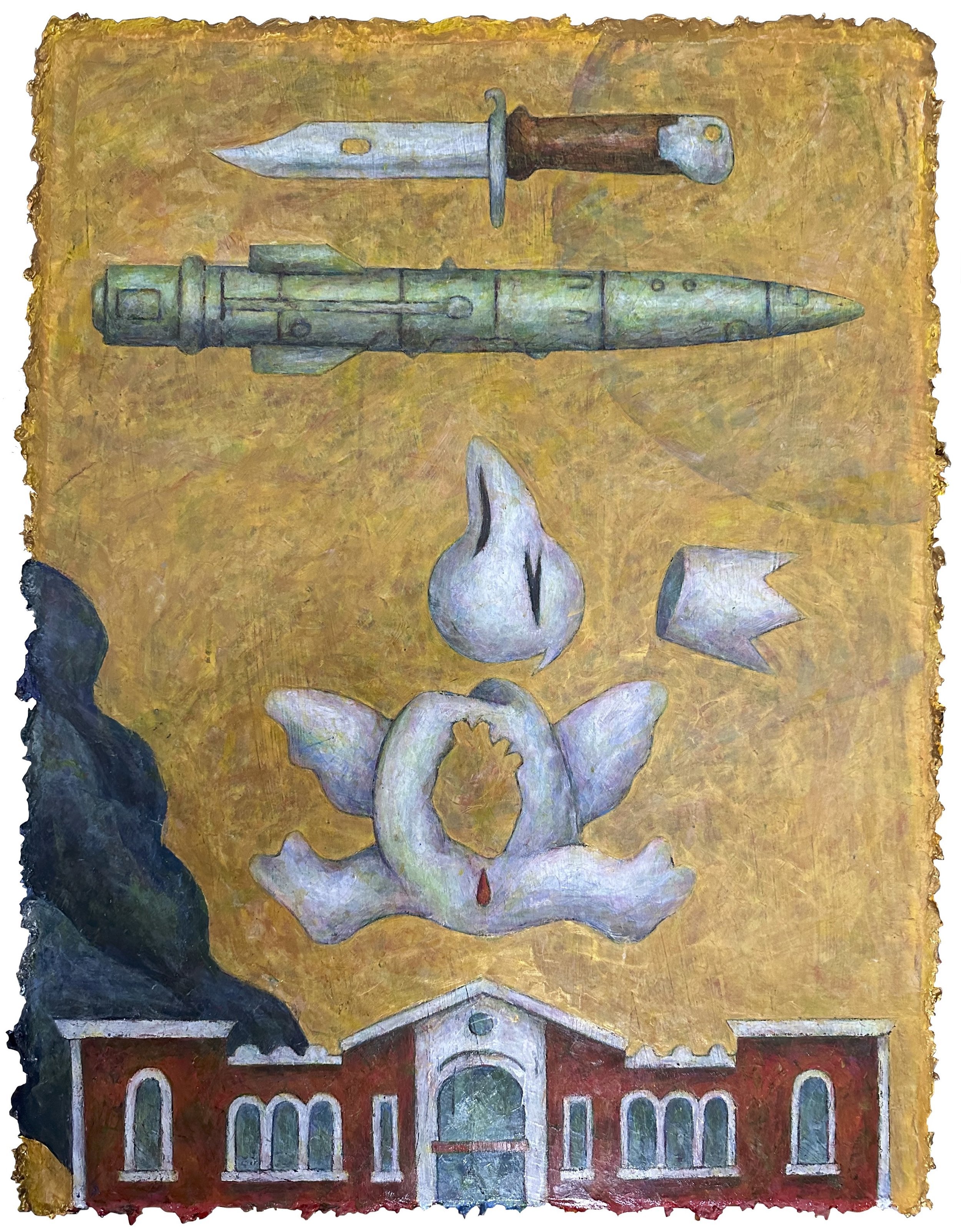

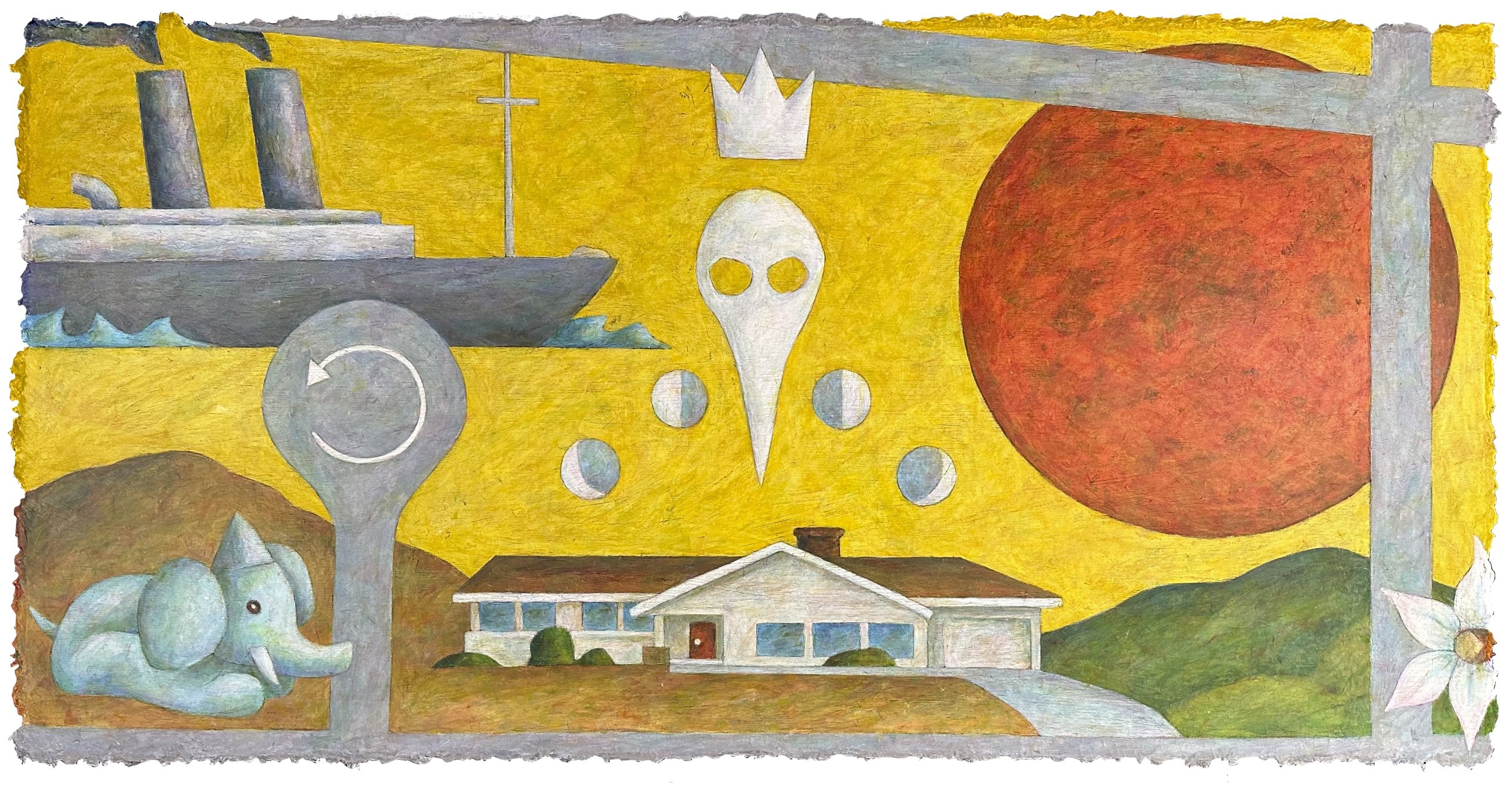

Most of my paintings are acrylic on wood, with the paint applied in thin layers (some opaque, some more transparent), scraped down, and reapplied hundreds of times to create an unusual depth of color. This also causes paint to build up and bubble over along the edges of the panel, so the work doesn’t need – and shouldn’t have - a frame. I love the way multiple colors can be seen in rocks and trees and bird’s wings and old signs on buildings. In museums and galleries, I also like to look at paintings extremely close (guards will often say, “Get back!”) to explore the choices and real moments that the artists experienced. That’s part of what drives me in this labor intensive and immersive way of painting.

I also recently finished a 32-part series of small paintings on artboard that connects the 1941 massacre of Jews at the Babyn Yar ravine in Ukraine to a wider cycle throughout history.

How has Katsushika Hokusai influenced your work, and in what ways do you resonate with his philosophy of continuous learning and improvement in art?

Some things just hit you in the gut and you can’t fully explain why. There are other artists (and musicians, writers, filmmakers) who have this effect on me, but no one to the degree of Katsushika Hokusai (1760 - 1849). Like Mark Rothko, he found his full expression late in life. His amazing print series, “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” was done around the age of 70. The sharpness and expression of his line and composition, the sense of people immersed in nature, and the texture of the ink and paper in his work fills me with continual awe.

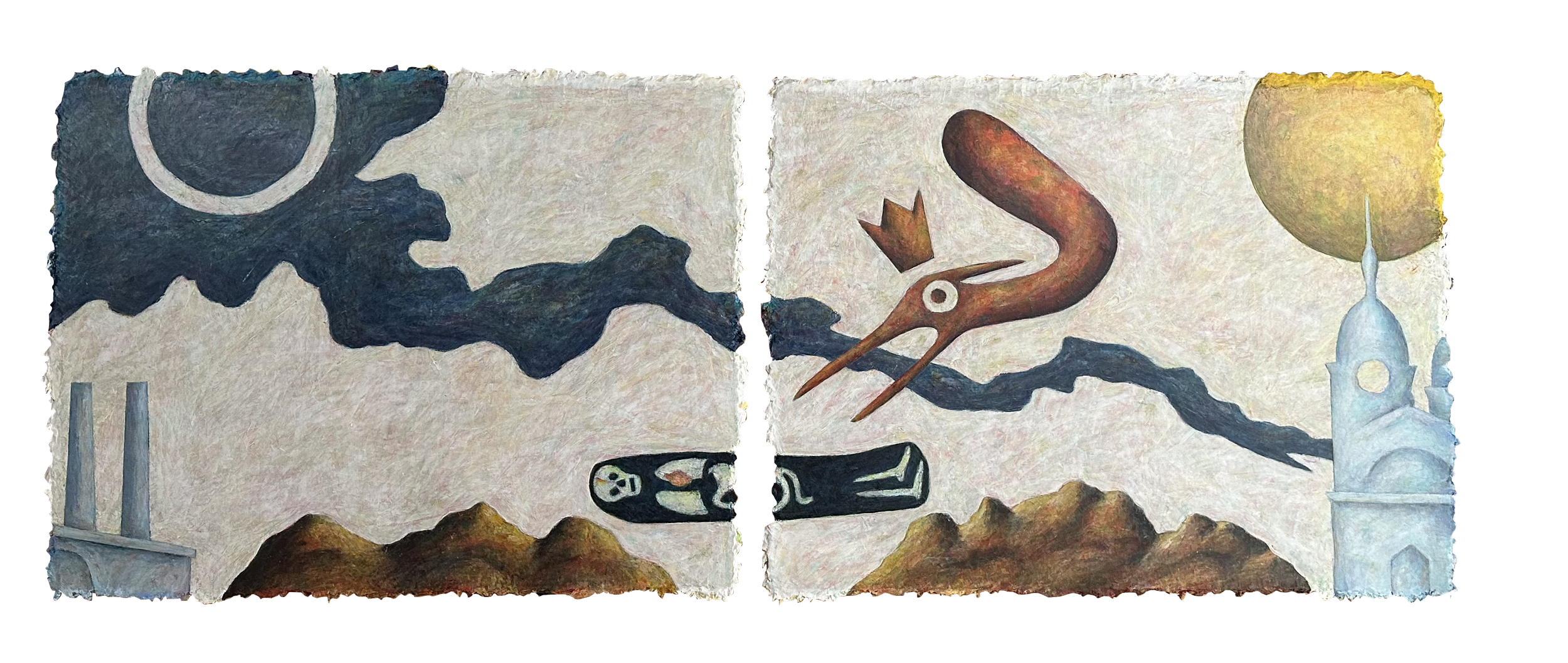

Your paintings often feature the Nahuatl deity Tlaloc. Can you elaborate on how your time in Mexico and exposure to Nahuatl culture influenced this choice and what Tlaloc symbolizes in your work?

The Nahua are in many ways the direct descends of Aztec culture and language in Mexico. Through friends who spent decades living with them and preserving this history, I had a chance to film several times with an esteemed Nahua ritual healer. It was an incredible experience to be a part of (and document) ancient practices that continue to have great meaning. Tláloc is the deity of rain, fertility, and nature’s balance. In this ongoing series of paintings, Tláloc represents many different faiths and the question of what, if anything, is beyond the world we see.

How do you balance your artistic pursuits with your activism, particularly in projects like the #FreedomButton campaign and your documentaries on human rights?

It all fits together. On a practical basis, I get up early and work on special projects until about noon, then paint until 6pm or 7pm. It’s also extremely important to find meaning and joy outside of work!

How has your style evolved over the years, and how do you think your experiences in filmmaking and journalism have influenced your artistic expression?

I keep trying to push my work into new approaches and learn from other artists and traditions. Over the years, I’ve met and worked with an incredible array of people, each who offer their own lessons about how to live a creative life. We made an American Masters documentary about the great playwright and LGBTQ rights advocate Terrence McNally (“Every Act of Life”), and I loved Terrence for his tireless commitment and his deep conviction that art can push society forward.

To return to Hokusai, he wrote in his 70s “From around the age of six, I had the habit of sketching from life. I became an artist, and from fifty on began producing works that won some reputation, but nothing I did before the age of seventy was worthy of attention. At seventy-three, I began to grasp the structures of birds and beasts, insects, and fish, and of the way plants grow. If I go on trying, I will surely understand them still better by the time I am eighty-six, so that by ninety I will have penetrated to their essential nature. At one hundred, I may well have a positively divine understanding of them, while at one hundred and thirty, or forty, or more I will have reached the stage where every dot and every stroke I paint will be alive.” Reaching that age may not be obtainable, but making every line – and every moment – become fully alive is a terrific goal.

What have been some of the most profound insights or lessons you’ve learned from directing and producing documentaries about overlooked or underserved communities?

It’s crazy to me that so many individuals and countries want to keep away (often through great cruelty) people from other traditions. Virtually every leap forward, from pasta to Impressionism to Jazz to the Covid-19 vaccine came about through the connection of different societies and cultures.

Are there any specific themes or stories you are eager to explore in your future projects, either in art or filmmaking?

Yes, but that’s a bit private until it happens. Mostly I want to get better as an artist and person.

Given your diverse and successful career, what advice would you give to young artists and filmmakers who aspire to use their talents for social impact and human rights advocacy?

Whatever you do, whether it’s in human rights, art, politics, or business – treat others, and yourself, with care and respect.

Instagram: @jeff_d_kaufman