Interview with Lucas van Eeghen

Lucas van Eeghen: the Artist's Journey

Lucas van Eeghen lives and works in the outskirts of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. His artistic activity mainly focuses in the field of painting, a discipline he approaches with originality, recovering the typical technique of traditional craftsmanship and by experimenting with personal and never conventional forms of three-dimensional expression. Lately he has been called the protagonist of nature, creating art transformed by nature. Or is it nature transformed by art? He prefers acrylic colours, tempera, oils, pure pigments and mixed media as pictorial tools, through which he develops suggestive paintings and three-dimensional works, from which transpire atmospheres that are floating in time and spaces. He has been amongst others awarded a "Lifetime achievement award” at the Triennale of Visual Arts of Rome, 2017. He exhibits a.o. in New York, Monaco, London, Amsterdam and Rome.

Representing Gallery in the Netherlands: Galerie De twee pauwen

Website: https://lucasvaneeghen.net/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/lucasvaneeghen/

What initially drew you to the magical-realistic tradition, and how did it influence your early work?

Born in the 1950s, I grew up at a time when the popularity of surrealism was at its height with Breton, Dali, Ernst and Magritte and, in the Netherlands, Willink and Pyke Koch. I think what attracted me then was that the boundaries of the rational were exceeded and a new, more intuitive way of perceiving was created. After a failed love affair, I bought brushes and paint and started painting from one day to the other without stopping. In my very first clumsy attempts, the admiration for Dali, De Chirico and Willink was clearly visible.

It was clear to me that I had to learn and work a lot to be able to create what I wanted. The painter's book Max Doerner, the portrait painter Karel van Veen and the academy Psychopolis in The Hague helped me on my way.

Can you describe the journey from your initial magical-realistic style to developing your own unique visual language?

I find it hard to talk about a fixed style or language of mine since I used and still use many.

An individual style has two aspects. It is a useful marketing tool for the recognizability of your own brand. It gives the viewer a frame of reference to be able to think in boxes. But it also invites you to linger in what you once invented with some success. For example, I wonder what was the reason for Mondrian to make his revolutionary losangique – as a writer-friend calls them - 'tea towels' for more than twenty years? Sure, he secured his income and status. And in the end he made his glorious Victory boogie-woogie.

For me, a style is foremost a vehicle for what you want to say. The unparalleled all-rounder Picasso showed this inimitably by constantly changing the way he depicted things. The portraits of, for example, Olga Khokhlova, Marie Therese Walter or La belle Hollandèse are completely different in style and therefore express something very different. The various ways in which I have painted along the way - sometimes at the same time - do not feel like searching for a style but as the way in which something can best be depicted. So I changed styles.

That said, it is true that my early works rub against magical realism. It is a large group of works that, in their chromatic and stylistic choices, refer the Dutch masters like Johannes Vermeer. The Dutch and Flemish light. Some of these frame the silent metropolitan views of Amsterdam and New York:

the public buildings like the station of Antwerp:

dwelling on interiors with long perspective corridors, or on the doors of entrances to halls:

or on the twentieth-century furnishing details of cafes and restaurants:

The same thematic series includes paintings dedicated to the Netherlands such as the huge panorama of Amsterdam, and the decay of churches like the Dominicus church in Alkmaar:

In the portraits and family scenes I tried to investigate a more daily and close reality, that also touches more intimate and expressive strings like a portrait of my son or my mother.

In fact alienation, loneliness, poetry, love, decay or death, are recurring themes in my works. But the themes are by themselves less important. For me it are always the individual paintings that give meaning. I suppose the most successful paintings have each their own secrets. Such secret is the wordless intuition that led to the secret. Maybe that is what remains of Surrealism in my paintings, without the spelled out rationalization and generalization of the subconscious. In fact it is not always exactly clear to even me what the embodied secret is. At some stations, for example, several buyers appeared to be dealing with trauma from the Second World War. Realising this made it a bit more clear to me what was hidden 'between the lines'.

But for instance with the café interior Welling it is still not clear to me why I am enchanted every time I see the painting in real life. I suppose, when I was making it, I couldn't have sensed that years later I would coincidentally meet my then future wife in that café.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced in moving away from established traditions to create your own style, and how did you overcome them?

In my search it turned out that at least surrealism was not what I was looking for. Take Dali's most famous painting with the soft watches, The Persistence of Memory. It is a technically and, above all, an intellectually very clever painting. Despite the strong symbolism, which refers to major topics and fits the era of Sigmund Freud, this form of surrealism is nothing more than what you see. As far as I am concerned, the rationalization of the subconscious does not evoke any emotion or insight. It has no hidden secret or enchantment, as for example the Arnolfini Portrait by the Flemish Jan van Eyck has for me.

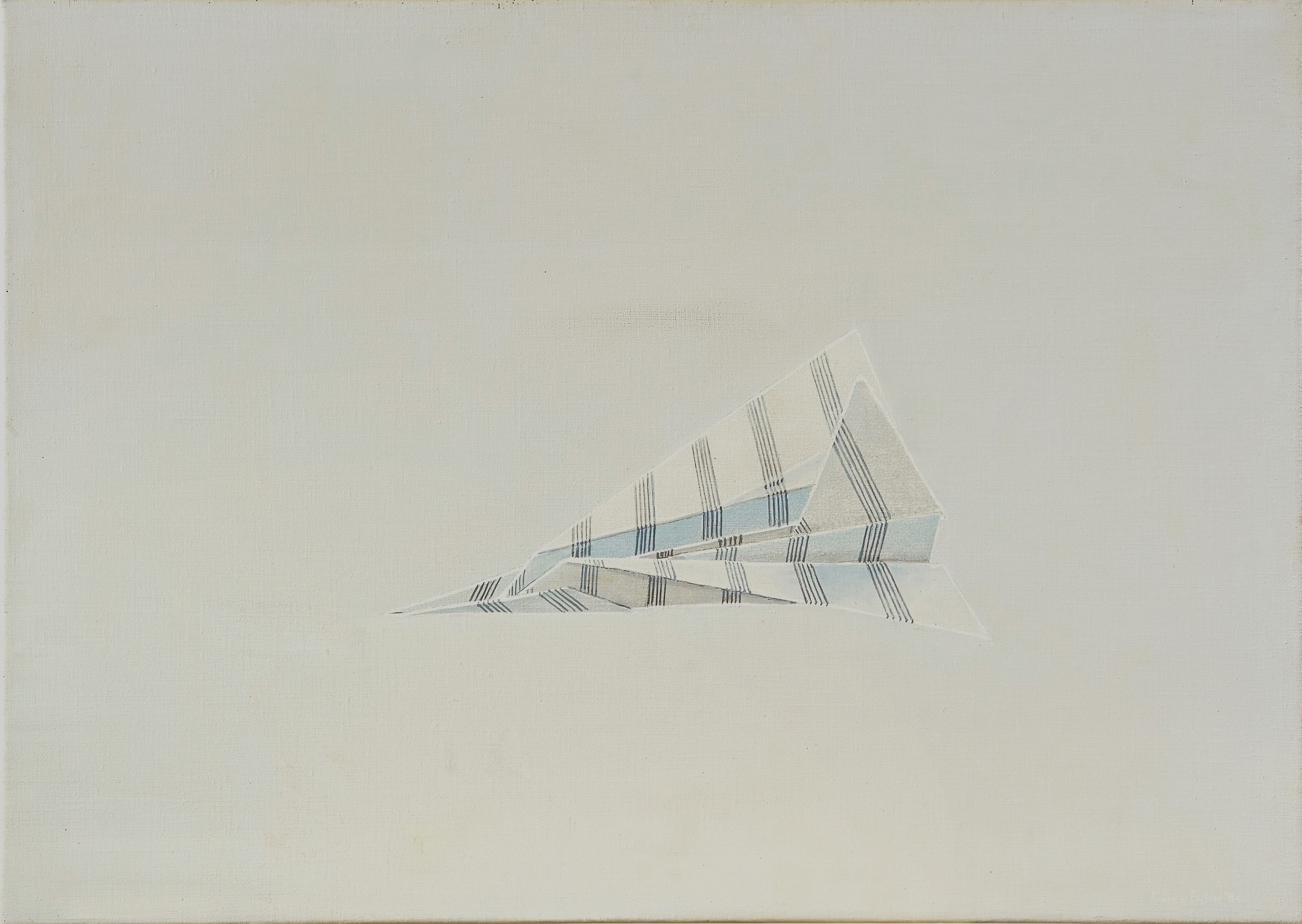

What I was apparently looking for, was an intuitive connection with an image. Trying to make the inspiration itself visible. Inspiration is elusive. As Mick Jagger says, it floats through the air. You have to notice it and pick it when it is there. After that it goes its own way when concretizing the image (or in Jaggers vision, the song). Artists know, the starting point of art is elusive and personal and in that sense magical. It is the floating yet unwritten song:

At some point I thought painting in the realistic trend was becoming too much of a trick. The inspiration was too overgrown by the technique I had developed. I had to look for another access to my intuition.

The Dutch Gallery Siau was one of the first galleries that committed itself to the revaluation of realistic painting in the Netherlands. He showed my works already at a young age. And represented a series of well-known Dutch artists such as Kees Maks, Jan Van Tongeren, Jan Sluyters and Carel Willink. To his initial dismay, I largely broke with realism after four successful exhibitions. I thought music was actually the highest form of art, because it was able to respond directly to feelings with minimal resources. Music can easily evoke moods that cannot be captured in words. We are highly trained to interpret what we see into something rationally coherent and understandable. Even if the objects are moving and thus changing all the time. The perception of music is different from the rational interpretation of images. I wondered if the non-rational perception could also be approached with images. To achieve this, I looked for other techniques and pure colours. I investigated to what extent pigments can be used as much as possible in their pure form - i.e. with a minimum of disruptive binders. The images became abstracts. The most special thing for me was that abstracts have a life of their own. As soon as something is on the canvas, that image will, if you look closely and openly, dictate how to proceed. Or as Rothko said: 'you never know where your work will take you.' The choices regarding which direction things should go, of course, remain very personal. Only you can recognize your own choices.

Eugène Siau deserved a big compliment because he continued to represent me in his stable even though he was really into realism. Fortunately for him (and for me) not entirely without success. The connection with the music apparently succeeded. The famous conductor Ricardo Chailly wanted to buy the triptych when he was visiting the collector/violinist who had previously bought it.

And the composer Louis Andriessen was dancing for Blue & Red at the opening:

The strongly coloured paintings that did not resemble paint had a spiritual charge. Without consciously knowing this I went in the direction of American Expressionism. This development was not over yet.

How would you describe the unique visual language that you have developed? What are its key characteristics and motifs?

After long walks with my dog, I increasingly felt a necessary connection with nature. This is of course not new. Monet and Van Gogh tried to depict the strength of nature vigorously. Nature ultimately is everything and determines everything. My need to incorporate this was made difficult because realistic flat pictures have too little independent meaning for me. Especially after photography in general was elevated to Art with a capital A and people tried to make photos to look like paintings. To my opinion the meaning of images has been enormously devalued by photography. Images have often become easy snacks. Even if the performance is extremely constructed.

So, I thought my images of nature should be tangible. I bought pruning shears and gave it a try. It turned out not to be easy to make a good painting with three-dimensional objects. Painting is not painting red tulips red. Nor is it a matter of painting over the shadows a bit darker. Natural elements fade or decay. And the relation of a three-dimensional painted object with a two-dimensional painted canvas appeared to be quiet tricky. A lot to explore and conquer. No wonder, my first tries failed.

Your work is renowned for its deep connection with nature, often transforming natural elements into artistic expressions. How do you choose these elements, and what process do you follow to blend nature with art seamlessly?

To conjure up lasting objects with fragile nature is no easy feat. This requires many different resources - mixed media I suppose that is why I have been described as the alchemist of the twenty-first century. But that is only technique. What it really is about, is creating intuitive images from nature. The first successful tangible but very precarious attempt was the poetic butterflies picnic, celebrating springtime:

After that I really delved into the three-dimensional space coming out of the canvas with some 60 cm or more. Some titles reveal the intuitive background like Field of hope or Night shelter:

Looking back, I am amazed that at one point I collected leaves in all sizes and, without any preconceived purpose, processed them, fitted them with stems and painted them white. Suddenly I knew. I bought a white foam panel, mounted it with a canvas and put it outside on my easel. At the end of the day an Enigma (which means riddle) appeared purely intuitively.

This 'riddle' of Enigma was largely revealed in the jury report for the oeuvre prize on the occasion of the Triennale of Roma 2017:

'His unique approach is synthetic yet simultaneously baroque. Nature is crystallized, embalmed, elevated to eternity. His work invites one to feel and touch, to unravel the mystery of nature and art. Van Eeghen is the alchemist of the twenty-first century. He rediscovers the traditional bond between artist and the imitation of nature by creating works that transform the natural element. In the past, art tried to reflect on nature by representing it in one way or another: Natura artis magister. Van Eeghen does exactly the opposite: nature itself is frozen and petrified where the dividing line between organic and artificial begins to evaporate. The work represents a longed return to the original harmony between man and earth and the renewal of what binds them to the origin of time.'

Nature is about zest for life and finitude at the same time. In my attempt to let art be nature and nature be art, I am indeed trying to resolve the difference between organic and artificial and showing, we, and everything, are all, will be, and have always been, part of the miracle of creation. I try to use the inimitable magic of nature as part of the secret in my art by letting my art be transformed by nature. To this extent, my attempt to elevate nature itself to art is, in all modesty, something completely different from the unparalleled beautiful attempts of Monet or Van Gogh to portray nature itself in all its power.

In its almost monochrome character, the 3D painting So blue emerged from a gigantic autumn leaf of almost 2 meters high and wide. When I found the leaf, the painting itself was immediately born in my head.

In the almost, but not quite, monochrome leaf-shaped paintings that followed, the spiritual meaning and inner light of each colour played an important role. In fact I went back to the earlier abstract paintings with almost pure pigments. As the great Monet has shown better than anyone else in his almost abstract Nympheas, colour has a great suggestive and contemplative power. But in painting, colour is technically also the enemy of a richly defined form. I suppose that is one of the reasons why Rothko preferred to paint his intense colours as semi rectangles without any suggestion of perspective. With my use of three-dimensional shapes of richly structured leaves, even the saturated colour becomes tangible in my paintings. A dimension is literally added to painting. A dimension that f.i. a photograph of my painting cannot show.

Is there a personal or emotional significance to the unique visual language you have developed?

As the revolutionary cubist and nature lover Braque once said it’s about being ‘in tune with nature.’ In my humble attempt to let art be nature and nature be art, I am indeed trying to resolve the difference between organic and artificial and showing we are all part of all aspects of creation and demise. I call that out, by using the inimitable magic of nature as an important part of the secret in my art. I do so by creating art transformed by nature and nature transformed by art. With the use of three-dimensional shapes and saturated pure colour I have added a new dimension to my tangible paintings. I hope that, In their spiritual appearance, they may shape our multifarious natural aspirations, such as hope, love, sadness and so, so many others.

But that is up to the viewer. Because paintings, once finished and exhibited, become owned by the viewers with an infinite multitude of interpretations. The natural species of mankind has a unfathomable creative mind. Indeed, by nature.