Interview with Maria Aparici

How has your great grand-uncle, Manuel Benedito Vives, influenced your artistic journey, and in what ways do you see his impact on your work?

In Maria Aparici Vives’s work, one notes a distant but suggestive pictorial connection with her grand-uncle, Manuel Benedito Vives (1875-1963), a painter of the Valentian school, especially in her female portraits in which each artist articulates a certain concept of style in accordance with the nomenclatures and vicissitudes of his/her time.

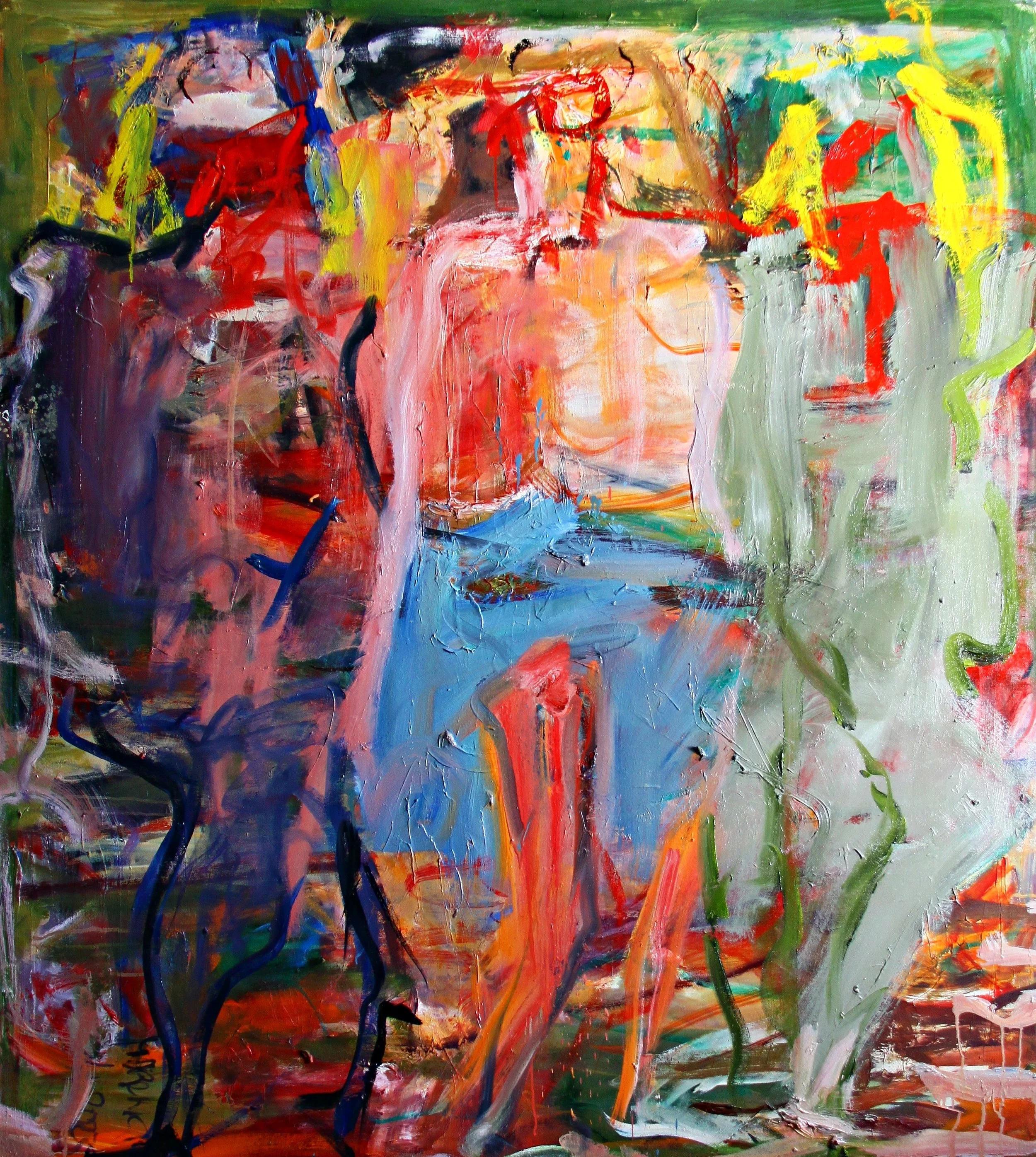

One might argue that what is in him an orthodox and sober characterization of bodies and atmospheres, Aparici’s work sets an expressionist and algid formulation of this same gender in boiling gestures, streaks, expressions and colors. They indicate an evolutionary tendency which leaves the eye with a creative vitalism in the times of different generations. Gregorio Vigil-Escalera (Spanish art critic).

Your studies took you from Burgos to the United States, and now you continue to learn in Madrid. How have these diverse cultural experiences shaped your artistic perspective?

For me, life is art. We live seeing and learn by observing, we are spectators of whatever place in a certain epoch, and in a relatively short time where artists can create.

I am a woman and, like with the majority of my generation, history has not been generous in flattery.

I have created an archetype of grotesque woman from spirit, but using subject, moving between concept and symbol, thought and reality, sensitivity and action, creativity, energy and mostly imagination which shouts revolt because not even an existence rich in experience, sometimes anxious but of an enriching globality has been able to convince.

Your work is characterized by a blend of expressionism, abstraction, and figuration. Can you explain your process in merging these styles to create your unique form of protest art?

The romantic expressionist artist has an amazing creative instinct but his/her worst characteristic is the colored evil. On the other hand, abstraction eliminates the relationship between form and background and induces confusion. The detour of different realities also confuses, even if it tends to express the vitality of an epoch with more clarity.

In my work, the three styles that are united in my personal seal complement each other: the same and unmistakable chromatic style, strong stroke and violent form, romantic sensitivity expressed by a hard and dreaming hand which moves the wetted bristles of the brushes.

Women are a central theme in your art. Could you elaborate on how you use the depiction of women to communicate your views on gender equality and feminism?

Art, before beliefs and convictions, is constituted by despair, regrets and sadness which normally make up the agony that precedes creation. Creative women during the course of history have been practically erased from the map by the man who considers us decorators without artistic sensitivity.

Thus, with my masked feminism, I speak with men but also with the female gender. In my timeless archetypes of women there are three well structured concepts: First, I criticize man and his mythical ideal of beauty, created and revered throughout history. Second, by creating grotesques, I criticize woman for selling herself cheap and losing composure. Thirdly and most importantly, I emulate this nostalgic and silent part which I support unconditionally, this lost group which society has abandoned to the loneliness of their own incoherence.

For this, I portray this difficult impartiality in images of unreal, diabolic and precarious women, ambiguous and most of all nostalgic of a worthy and recognized history.

The aspect of my painted women is sometimes disgusting compositions which are sketches that have been automatically extracted from the shadows, distorted forms which I synthesize in enigmatic characters that are charged with energy reinforced by contrasting pure colors. From there the rage of the grotesque because I believe our history is just that. I am voice, vote and sincere model, I identify with them.

A contemporary reading of the painter Otto Dix’s work, at least if done from a gender point of view, leads one to the conclusion that the author was a genuine misogynist. With assiduity, he represented scenes of extreme violence, with women as protagonists. On the other hand, the artist Maria Aparici Vives, in the eye of some professionals of the art world, creates somewhat sexist works showing women with a certain grotesque or even ridiculous aspect. However, the sensationalism achieved through her explicit works is not geared towards laughter and derision but the exact opposite. She resorts to a satirical formula in order to plastically materialize the problems of the woman of our time. The sordid part of her work embodies the need to break the standards of beauty imposed on women by the ongoing phallocentrism, at the same time breaking the esthetic beauty of an academic wink in the work of art. Finally, her recent trajectory centers around making visible the question of female beauty created by a patriarchal culture; exhibits the obstacles and the drift towards -grosso modo- grave consequences which we women of today suffer in order to accomplish such standard of attractiveness, making us aware of the, sometimes subtle, ties which still constrain us. (Art critic Andrea Garcia Casal, Miss Goethe)

You've mentioned that simple distortion in your paintings signifies resistance. How do you decide on the level of distortion to use in each piece, and what does it symbolize.

Great works must count with the cruel and monstruous, combined with the faustian dream of reason and the trap of intelligence. The expressionist artist distorts in order to emphasize decadence, gives priority to that which his/her subjective expression perceives but without getting to caricature which, paradoxically, is the first subjective impression which comes out of a spontaneous note. But I don’t do notes or sketches, previous drawings or meditations, mirrors or copies. I launch myself directly to the canvas or various canvases simultaneously, like someone who jumps into empty space.

My work is an abbreviated blow, real, spontaneous, deformed and elegant which describes this world of farce.

Lavater said: “Trust everything to your first and most rapid impression”. Sometimes my rapid, deformed and unfinished figures in their aspects transform reality into a historic abbreviation which is exactly what I feel about our female existence.

Your art reflects a range of emotions, from utopian joy to overwhelming misery. How do you balance these contrasting emotions in your work, and what role do they play in your creative process?

We have engulfed the cultural and artistic past from different opinions and had no other choice but to continue creating. One of the ways for civilizations to express themselves has been through forms and I have chosen this and its grouping. Which means to say that form has made of me a style.

But art has no other finality than conceive itself progressively and in permanent mutation over time, and it does so in case by way of invented forms. I am adult in knowledge and to legitimize once again this art as my own is by way of the power of memory, life, culture, history, pain, expression and most of all of meaning. Art always presents us with a dialogue because its signs of identity are as old as our history which, in the end, is mine. As a woman I am concerned about our success and failures. Taking me as a model, it is said that beauty is love and tenderness, but the sublime surpasses any aesthetic characteristic. Not only is it found in beauty, but also in that which is anecdotic, horrible and disgusting, not only is it energy, it may be also moderation.

You have had your work exhibited internationally, from Spain to India. How do you feel audiences in different countries respond to your art, especially considering the universal themes of gender and struggle?

The history of my painting has been a constant innovation, a development populated by breaking off, advances and new goals, and at the same time it is the fruit of suffering, doubts, fears and abandonments. This mottled set of modes and fashions converts itself into signs of a society in hectic evolution. There is no myth without its contrary vision. The acceleration does not rest, and any proposal vanishes before becoming viable. With my painting, I definitely tie myself to this changing world and I don’t know what will happen.

Among the numerous awards you've received is the Premio Scienza del Museo d’Arte e Scienza of Milan. What does this recognition mean to you, and how has it impacted your career?

Art is not a science and as such has no patterns, rules, procedures etc., unless the artist himself/herself imposes them. I showed some of my work at the Milan Museo d’Arte e Scienzia where some of Leonardo da Vinci’s treasures are kept. The impact on my career was the satisfaction of having shared space with the great master of the Renaissance.

Your work is part of both corporate and private collections. Do you feel there's a difference in creating art for these different types of collectors, and if so, how do you navigate these differences?

With the years, duration and time go hand in hand. Like I said at the beginning, the artist self-imposes the responsibility in accordance with the epoch and the environment in which he/she lives.

I started out very well, international collectors bought my work and later the capricious spectator or the preconceived establishment relegated me to oblivion. Actually now, the sensitive, younger look by enterprising and brave women is rescuing me, sees my art and understands what I want to say and show, perceives this identity between discord and harmony, between being and having, composing and breaking, contributing and diverting, and makes me happy because it has nothing to do with women of my generation in Spain.

As you continue to live and work in Madrid, how do you see your art evolving in the future, and are there any new themes or techniques you are eager to explore.

When we observe the killing in Ukraine and Gaza, with our eyes white of dread, we associate artistic encouragement with dark, black color. A painting is the image of any nation in the world, we perceive its color as a sensation and a feeling. I paint emotions of hope with colors of feeling, and in them you find stages of mood, anxiousness, pleasure, pain, affirmation or negation. With form we reflect, we understand it (or not), we value it and we are surprised by its physical and spiritual capacity. I would like to keep surprising. The men who see it all in black should know how to color things, less conceptualism and give up the ephemeral changing fashion.

For me, art is the great adventure of spirit and mind which, observing past achievements, reinvents itself, rediscovers the past original and creates something new in the present.