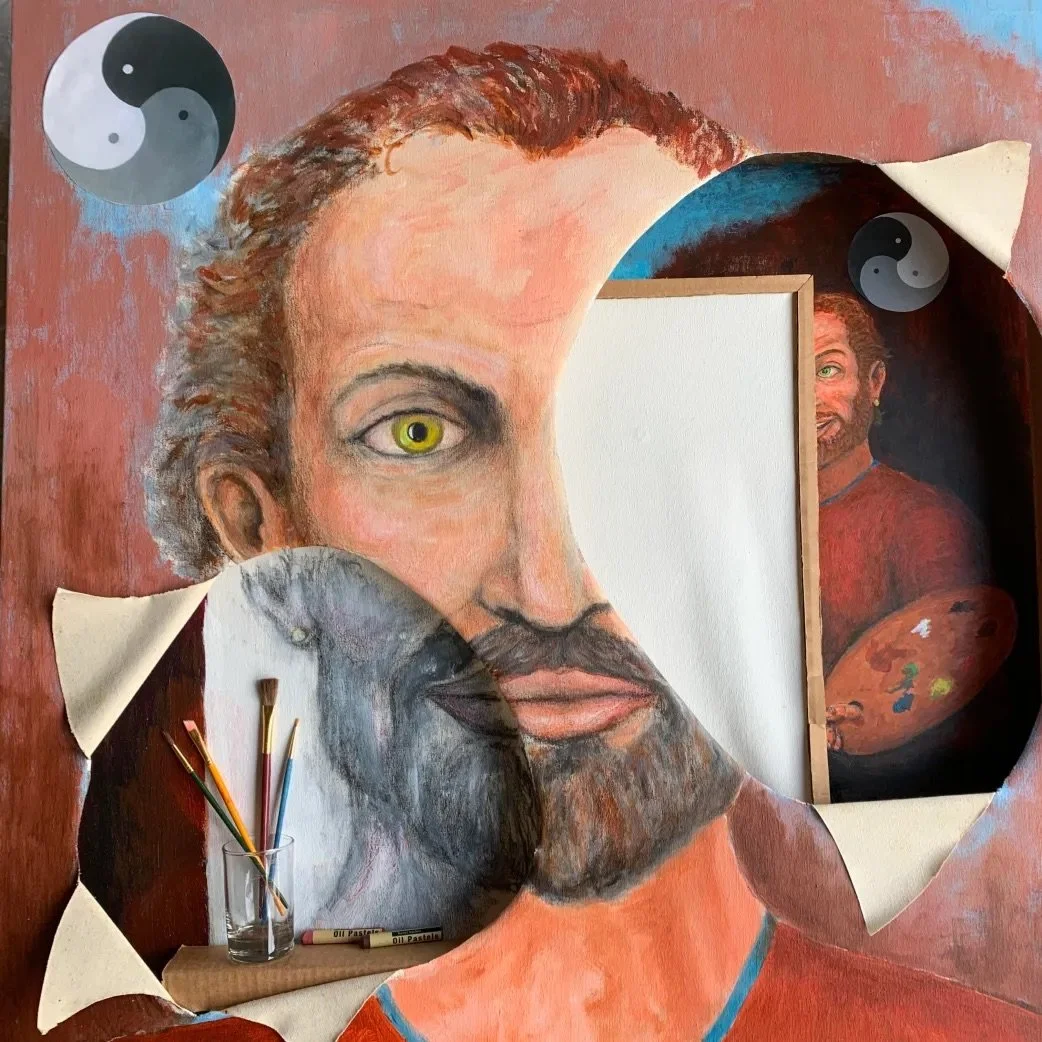

Interview with Patrick Webb

Triumph of Punchinello 200x48

Patrick, your academic background includes an M.F.A. from Yale University, study at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and a B.F.A. from the Maryland Institute College of Art. How did your time at these institutions shape your artistic vision, and can you elaborate on any particular experiences or mentors during this period that had a profound impact on your development as an artist?

I went to MICA at my mother’s insistence—she was an artist and believed that if I was to be a painter, I had to learn to draw. MICA had great drawing instruction. While there, I began classes copying from paintings in museums. We tried to figure out how the paintings were painted (underpainting, overpainting, direct color, etc.). The instructor Israel Hershberg opened my eyes to the enormous scope of painting. I went to Yale to study with William Bailey because he painted from imagination. My experience in undergraduate and in the museum convinced me that what I wanted to acquire was the capacity to form a pictorial world through which to tell stories. I struggled tremendously at Yale. When I graduated, Bailey came up to me and said, “Now you can go learn how to paint.” He was right. I spent the next four years teaching in the Midwest, working out how to build a pictorial world.

Your work often grapples with the AIDS crisis, a subject both personal and universal. Can you discuss how the experiences and emotions surrounding this crisis have evolved in your paintings over the years, and how you balance the expression of personal grief with broader social commentary?

HIV disease was the second great event of my life, the first being coming to terms with my sexual orientation. The HIV epidemic and same sex desire inevitably became interconnected for me, and came to shape my singular experience of Eros and Thanatos. Since I believe that art shows us who we are, both of these driving forces had to be in the work. But to find a way to do so that was not anecdotal or maudlin proved to be a challenge. I found in the art that impressed me the most (music, poetry, literature, painting) used a measured formal language that created at the same time both tension and clarity. So, in all of my work, I build worlds that allow me to explore the intimate and mythic dimensions of the narratives.

Your paintings are noted for their narrative quality and rich symbolism, often incorporating elements from Christian martyrology and carnival imagery. How do you approach the process of integrating these diverse references into a cohesive visual language, and what do you hope to convey through this layered symbolism?

The poet Stanley Kunitz, who I got to know in the last decades of his life, talks about finding myth in autobiography. Nietzsche points out that for the modern subject there is a terrible problem with the loss of a central religious myth. How do we find the essential qualities of existence in our own lives? I start with a specific story I know or have experienced, and then I expand it into myths I know. The world of the painting—with its synthetic structure of color, value, line, etc.—creates the integration of the myth and the story

The Punchinello figure is a recurring motif in your work, representing various facets of the human condition and queer identity. Can you delve into your initial inspiration for using Punchinello, and how this character has evolved in your paintings to address different themes and narratives?

I first came upon Pulcinella in the paintings and drawings of GD Tiepolo, son of the more famous 18th-century painter Battista. I fell in love with this clown from the Commedia dell’arte with his phallic red nose and conical hat. I wanted a repeatable character to whom the narratives of my paintings could happen—an I not I. My version of Punchinello is different. He has no hump and the mask is similar to Il Capitiano’s, another character from the Commedia dell’arte, one who is powerful and brutish. At first, my Punchinello was doomed by HIV but as I have survived so has he. Lots of things have happened to him. Some of his experiences are quotidian: working out in the gym, marching in parades, lolling on the beach at night, swimming in the swimming hole, playing cards, or celebrating a festival. But Punchinello also confronts authority. He fights for rights, gets caught in the cataclysmic fires of a boiling earth, and most recently throws himself from a bridge with his lover to escape murderous homophobia. This most recent series of paintings emerged after I encountered the story of two young gay Armenians, whose suicide in October of 2022 seared my imagination and became a central theme.

Your work draws from a wide array of influences, including the Commedia dell’Arte tradition and artists like Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo. How do these historical and artistic influences intersect with contemporary issues in your paintings, and in what ways do they help you address the complexities of modern queer life?

I am an American painter and for Americans there is a short artistic history. We are a melting pot and as such I take the liberty to borrow—or even steal—from everyone and everywhere. I feel lucky to have found the things I need for my expressive endeavors. James Joyce speaks of walking on the beach and his foot striking the rock he needs. I think of these elements as such.

As an artist who has consistently explored and redefined themes and techniques over the years, what new directions or projects are you currently contemplating? Are there any emerging themes or subjects you are particularly excited to explore in your future work?

Several technical things have emerged in the last years. My color maker has been grinding some new pigments that excite me and have entered the palette. After a period of discomfort I have found a treatment for my arthritic shoulders that has allowed me to paint large again. The “Falling Armenian Series” has been fascinating because as I paint and repaint their fall and then their landing I find myself reflecting on the multitude of meanings and references these moments distill. The Falling moment is one of intense intimacy and affection as well as a tragic act, a folie à deux, while the crumpled figures at the end are horrible in the extreme, my Charnel House. We seem to be a world on the edge of that tragic moment—maybe affection is our only way out.

One of the significant challenges you have faced is formulating a convincing figure type that balances vulnerability and powerful sexuality. Can you discuss the creative and conceptual hurdles you encountered in developing the Punchinello figure and how you overcame them to achieve the balance you desired?

I draw from life all the time. I like the physical and erotic presence of the model. I use the drawings for reference, building compositions with them in mind and in front of me. But I do not paint from life. I want the gestures and compositions to be mind-made, not observed. So there is an ideation that goes on in arranging the shapes, colors, space, and figures to tell the story. In fact, I start with the composition and not the figures—blocking out rhythms of color, value, line, gestures—before any information about figuration emerges. The antecedents for my idea of the figure draws on a tradition that can be threaded from the 20th century in Jared French, Balthus, and Picasso in his classical period, through the 19th century with Seurat and Corot. The figures of Chardin seem part of this idea, as do late paintings of Georges de La Tour. They all originate in Bellini, Carpaccio and Piero della Francesca. I suspect that these painters, like me, were influenced by Romanesque figuration, which in turn harkens back to early classical sculpture. For me, the figure has to have a wholeness, physicality and simplicity. I am uninterested in portraiture. I believe in the dream author of the painting—everything in the painting is the artist (Freud).

Your use of Punchinello extends beyond personal narrative to critique contemporary mores and societal attitudes. How do you navigate the line between satire and earnest commentary in your work, and what role do you see art playing in challenging and reshaping cultural norms?

I hope that the combination of seriousness and play that I believe is central to the carnivalesque makes my work approachable. But I am willing to admit that the going can be tough. My favorite art is so—Titian’s “Flaying of Marsyas” is no walk in the park—Messiaen’s “Quartet for the End of Time” is not danceable. So I hope to paint paintings that provoke thought and trigger emotion.

Stanley Kunitz praised your paintings for their 'complex psychic texture.' Can you explain how you cultivate this psychological depth in your work, particularly through the interplay of irony, pathos, and the grotesque, and what effect you hope it has on the viewer?

I am always asking if what I am doing is honest. Am I fulfilling the impetus of the idea—finding the textures of the experiences and their complexities—after all everything I paint is mine. Studio time is making, thinking and unthinking. My viewer is someone who is ready to travel beside me on my journey. If they are not ready to go with me, I doubt I can say much to convince them. However, I do find people who are interested in art, in affect, and in experience, and who take from my painting something unique. I only ask that my work be taken seriously as an exploration of contemporary life.

Brian Kloppenberg describes your Punchinello as embodying the uncanny, a concept explored by Freud and Cixous. How do you use the uncanny in your art to create a sense of both strangeness and familiarity, and what do you believe is the significance of this duality in understanding queer identity and experience?

I believe that the experience of being alive is uncanny, so if art tells us who we are it does so by showing us how that uncanniness unfolds. I paint from imagination. I paint something that gets under my skin and I cannot move on until I have painted it out. Sometimes the story is the ordinariness of dinner together, other times it is the fury at homophobia, or the horror of a world on fire. But by using a measured visual language and including the Punchinello figure, a masked figure with no face behind the mask (Agamben), I believe my paintings grasp something of the uncanny; they are familiar and unfamiliar. I follow the road of the id.

Ecce Punchinello Swat 36X28

Falling Armenians 66X40

Four ages of Punch 60X48

Lamentation_and_By Punchinello's_Bedside 78x125

Love 60X48

Night Lovers II.50

Punch Battle 78X60

Punchinello Works Out Vanquished 44X56

Table Talk Spagetti 36X28

The Feast of the 7 fishes 35X60

Tinker Tailor Soldier Sailor 60X125

Warterfall Arcadia 60X60

Denis Cheats Punch 32X28