Interview with Paul Scott Malone

Photo: Self (2024)

Your career encompasses a remarkable range of experiences, from soldiering and bartending to journalism and academia. How have these diverse roles informed your approach to visual art? Can you delve into a specific instance where an experience from one of these roles directly influenced a particular piece of your artwork, shaping its themes or techniques?

More than anything, those experiences, when I was much younger and just starting out in life, have provided me with numerous encounters and characters to remember -- either to write about, draw or paint, often more as types than individuals, all rising from memory and an imagination looking for the spirit in a face or an action that lingers somewhere inside your mind. They also provided me with a much deeper connection to the broader populace of America. In Houston, I grew up in a rather insular, middle-class environment composed largely of banking executives (my parents, for example) and business people -- Oil People, as we called them -- and of course their families, along with the service folk who handled many of our needs. When I was young, my family went to church three times a week, i attended Sunday School before the morning sermon, went to Vacation Bible School at the church every summer as well as church camp on a beautiful river out in West Texas. Of my two best friends, one's father worked at a foundry and the other was a federal judge. Most everybody in the public schools I attended looked and sounded pretty much just like me.

Near the end of the Vietnam War, however, I got caught up in one of the last waves of American draftees, conscripts -- my lottery number was 8 -- and in 1972 when I entered the military I was suddenly exposed to all kinds of people I'd never known existed, from backgrounds across the Southland, and the Northland, as I was posted, after training, to a small Army battery on the beach in New York City. While I was there, I learned all I could about that remarkable place, and I visited New York's Museum of Modern Art for the first time. The world became a different place for me, full of new potential and new experiences. When I left the military in 1974 and returned to Houston to renew my college career, I took with me that introduction to the broader world. The famous Rothko Chapel is closeby the University of Houston and I often visited it and the other museums in the city. I went to college with the assistance of what we call here the GI Bill of Rights, which paid for most of my education but not quite enough to fully live on, so I started tending bar at a small downtown steakhouse. For those four years, I spent countless nights observing and listening to the lives of the various people who found their way to the barstools across the wood from me, not to mention all those barmaids and their tales. It also taught me a healthy work ethic, the discipline to make things happen, which I have followed all these years. In college, I rediscovered a talent for writing and so I also worked for two years at the student newspaper, The Daily Cougar. On graduation, I needed a real job, so I went to work as a journalist at a small newspaper in Texas before moving to a larger paper in Oklahoma City. After five years of reporting and editing the local and regional news, I had all I'd ever need by way of material for a lifetime of making art.

For the next fifteen years or so, as a graduate student and then a part-time academic and before turning to painting full-time, I devoted myself to writing short stories and poetry mostly about working- and middle-class people in Texas, all walks of life. I tried to understand why and how people face the challenges that always come in life, and I found that it's almost always related to love in some way. Love remains the most mysterious of our emotions because it wears so many masks, so many disguises, and it is so hard to comprehend beyond the natural need to reproduce and protect the offspring against a hostile, indifferent universe. In fiction, an enlightened narrator, following some inner voice that comes from deep inside, most always falls in love with the characters he or she is delving into, and it's again that dichotomy of chaos and conflict in life, and how our way out is so often the pursuit of help, partnership, change and intimacy. It can be brutal, and even violent, a savage embrace, but the heart can be a pugnacious hunter. All of that has carried over to my abstract work, and now again in my, as you've called it, "expressive" work. How we, in art, transcend the perils of life is by falling in love with our own characters, our interiors or landscapes, scenes, nudes, tigers, cityscapes, strange abstractions ... your model, your dog, your nation ... and we let that love speak in our work. It's the fundamental philosophy of fine art: to uplift by sharing ourselves with each other and thereby create a civilization based more on love than hatred, one heart to another. "Spill the beans on yourself," as Falkner advised. The viewer can see it in the artwork whether they know it or not, and we respond most fondly to those works that expose the most.

The best examples of artwork that rose from that time can be found among my pencil portraits, from a high school girlfriend to my drill instructor in the military. (See PORTRAITS on my website). A painting titled "The Pregnant Maiden and the Purple Urn" (1998, GRID series) also represents material from those early years mixing abstract elements with representational elements, and see my recent "Weeping Boy," (2024, PORTFOLIO) which goes way back to my childhood.

The American South and Southwest are prominent settings in your work. How do the unique cultural, historical, and geographical elements of these regions shape your artistic vision? In what ways do you strive to balance the inherent nostalgia of these landscapes with the infusion of contemporary issues and themes?

The American South, and the Southwest especially, each can be imagined in their unique nostalgias to great artistic effect, as uncountable Western movies have shown. The South, even in fine art, is often depicted as ignorant, backward and somehow corrupt for its distant past, while the Southwest is portrayed as the place to go and get crazy, a land of outlaws, wide open, amid some of the most spectacular landscapes and nightscapes on Earth, and where ancient civilizations still reside pretty much as they have for centuries. It's all about the seemingly empty but rollicking landscape out there, and the sun. The sun is so intrusive in Arizona that even shut-ins get tans in the summertime, and my dark brown hair became something like blond after living around Tucson off and on for fifteen years. Now it's silver-white!

What I mean is: I grew up in the meeting point between the South and the Southwest, where the two regions meld. Houston, a huge port city closely tied to other ports around the Gulf of Mexico, such as New Orleans, has mostly a Southern vibe - genteel pace in private gatherings, Southern urban accent and architecture, lots of pine trees and azaleas and the like, it rains all the time - but every Houstonian seems to want to own a ranch out West, in with the desert and the cacti. That's where I came of age, caught in the middle of these two highly distinctive cultures. To the north and east there is East Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida with all their baggage; to the west we find the expanse of West Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and Southern California dragging along all their baggage; and everything eventually comes bustling into Houston. Today, Texas -- roughly the size of France and known as the Oil Capital of the World -- is huge in many ways with the tenth largest economy in the world, three of the ten largest cities in the country and a population of every variety. Still, there are certain cultural and historical aspects of life that we cannot escape. And those nostalgias inform our Contemporary art in the same way nostalgias impact the art in cultures all over the globe. Even now, the American South, still grappling with the shadow of slavery and the Civil War, can be ignorant and backward, and the West, still grappling with its own conquering past, can be crazy with contemporary outlaws, but the universal themes always apply ... love, hatred, ambition, longing, loneliness, hope, joy, injustice, rage, failed enterprises, success ... and how they play out in each rough individual life is important to capture for the sake of art, so that every and any person can be seen as a star in the Contemporary world, no matter their imagined sins. The only real and permanent signifier of these lands is the way we say: "Hey, y'all."

Your journey into painting began in the wake of your mother's death. How has this pivotal moment, and the theme of mortality in general, permeated your work? Can you discuss how this personal experience has influenced both the subject matter and your overarching philosophy as an artist?

The loss of a loving relationship with one's mother is a devastating life event for most anybody. But for me it evolved as the moment I realized that if an early death could come even for my mom, a long desperate struggle for a woman who had always been a vibrant, loving woman, then death can't be far behind for me either, and my thinking about my own lurking, inevitable end moved to the forefront of my musings on life. The common realities of mortality began to enter my storytelling and my approach to painting. I came to see all human endeavors as a perilous but necessary battle against, first, the demeaning chaos and the swift current of a lifetime, and, second, the mystery of, and the fear of, death. Any sense of Christian redemption and salvation -- the very idea of a heavenly Heaven - fled my hopes and aspirations for good. I started to view life as both a Heaven, and a haven, in its own right -- the joys and delights of being alive -- as well as a Hell -- the many tough and damaging disappointments of living -- all of which must necessarily accompany that duality in order to create an equilibrium. Without despair, we wouldn't know happiness. Living itself blooms from the blood knowledge of death. As Dylan said, "Those who ain't busy being born are busy dying." It's just the universal, perhaps-never ending, life cycle and you may as well adapt as best you can in the pursuit of happiness, an elusive, abusive and extremely personal journey for everyone, a journey that could end in an instant.

That hard fact struck me again when my older brother died nine years later, in 2005; one day we talked on the phone and the next I got a call from a relative telling me that Rob had been murdered. At that time, he was a university lecturer in economics in Houston and only 57 years old. I was living in an old house in a little desert town outside Tucson, Arizona. The main studio had a gravel floor and the rafters showed above. For the next several years or more, virtually all I did was make abstract rage paintings, later disguised as nightscapes and the like, though I've lately revived the original title of one of the series, from "Origins of the Natural World" back to "Just Dance ... ." That term came to me as the best I could find to describe the deep-seated feeling of despair and anger brought on by the understanding that life is just that: a furious, unguided dance away from gloom and destruction as one awaits the arrival of the pale figure with a sickle in his hand. That's why we party so much! That's why we enjoy art and entertainment! It's why we dance! It's why we fall in love. It's an old theme, a universal theme to be told over and over again. but as I was making the twenty or so paintings that would become "Just Dance," I would carefully explain to my dead brother, as if he were hovering over my shoulder, each step in the furious processes I went through in those emotional and explosive works, all of them rich with color and abandon. Somehow, that made it all legitimate for me. I had earned my brother's revenge, his redemption so to speak, kept his memory alive, just by painting. For the first time, I had truly broken free of anything resembling realism, or even representation -- or even my conceptual work back then -- and entered an extended period of internal exploration, allowing my emotions full sway over my care for the rest of the living world. It led to a quite number of paintings collected in series format with titles like "Eruption," "Firmament," "Dark Matter ," "City Heat," "Extreme," "White Light," "Sand & Fire," "Just Dance ... ." It was the closest thing to a religious experience I've ever had. It made me see that my salvation lies in the act of making art, and leaving it all behind to face its fate alone.

Your mother played a significant role in nurturing your artistic inclinations and imparted practical wisdom on sustaining an art career. How do you perceive the concept of artistic legacy in your practice? Do you feel a sense of responsibility or continuity in preserving and extending the lineage of creativity that your mother initiated?

I inherited four of my mother's paintings -- she mostly did florals -- and her painting brushes. I still use the brushes, the tools, all the time. I just mixed them in with my own. In that way, I suppose, her work is flowing through mine and into the future. And my memories of her are still fresh in my mind. In the end it's all memory.

Having begun your career as an abstractionist before exploring other genres, how do you reconcile the philosophical and aesthetic differences between abstraction and representational art? What unique communicative power do you find in each approach, and how do they reflect your evolving artistic intentions?

When I say I am first an abstractionist I mean that I have done more abstracts than others. I actually started out -- when I made up my first sterious studio in Urbana, Illinois -- I was doing figure paintings and more conceptual works, for instance the work in the West series and the Grid series as well as the Figurative series. That was following my mother's death. When my brother died, I moved into a purer abstraction for many years. Over the years, as I integrated more and more ingredients into that work, and I once again became more interested in the human condition writ large, I started integrating abstract elements with bits of figurative elements and came up with what I'm doing now. It's a combining of two artificial approaches to art and combining them into one. Drips and splashes, color fields, line drawing, avoiding realism except in theme, many of the tricks the Modernists and Postmodernists used to create their allusions I have incorporated into my painting over the years. It was all a guess and an adventure, but it has advanced every aspect of my current work. The abstract elements inform the background without much adieu and they help highlight the foreground and present a grounded theme of the relationship between human life and the raw elements that compose all of life, the earth, the sky, and what lies in our hearts, as if we could ever understand that. Combining the elements of abstraction and representation aids a major theme of mine, being that everything we imagine is seen through a fog of memory. In memory, nothing is exact. In memory, we may see a face but it's always steeped in the abstract deceptions of reality that lead to imaginary depictions of what life could be, not what it is. I paint what I see with my mind, not so much with my eyes. That's when you realize you're painting for the next generation; you're leaping ahead of the crowd. And you're often going to be misunderstood and ignored. So be it!

With accolades from prestigious international institutions, how do you perceive the global art community's valuation of your work compared to that of the American art scene? Does this international recognition influence your creative process, your sense of identity as an artist, or the themes you choose to explore in your work?

Yes to all three of those questions. For the first time, I truly feel a part of the larger art world outside my cramped and isolated studio. It's not only from the accolades -- they just go to my head with new confidence -- but from the energy boost that comes from being sought out by, and then getting to work with, some of the world's most prestigious fine art gatekeepers, such as Art Curator. Just this year, since Art Curator last December called me a Top Artist to Watch in 2024, I've appeared in almost a dozen European art publications and three of my most recent pieces, things painted only a few weeks ago, are already in print. I now have an agent in New York, I'm on two online sales platforms, out of Paris and Lyon, with another coming online soon here in the States. We're also planning several exhibitions for later this year and next, from New York to London to Hong Hong and Miami. It's positively gone to my head and it has set me off in a new direction with my work. I have a strict routine now and even a strict schedule for the production of a number of works in progress, and now when I'm at work it goes joyously, almost magically, with so much spontaneity. It's all a big mind game. After thirty years of obscurity, squirreling away paintings in a warehouse that few people have ever seen -- in most cases works that only I have seen -- it feels like payback for a lot of personal investment and hard toil. So, what also goes to my head is the idea that I was right all along ... I was making Art, good Art, all those years ... out here on my out-of-the-way little patch of the Earth.

This new-found attention is an affirmation of that. Why it first came from Europe I'm not sure, but let me repeat a phrase that someone I admire once said: "In America art is a luxury; in Europe it's a necessity." Perhaps that's why. Or just good luck. Back in 2022, a charming young curator named Maria Teresa Cafarelli at ITSLIQUID Group in Venice came across me on Instagram or Facebook or someplace, went and looked at my websites, really looked closely, wrote to me, said she wanted to exhibit two specific older paintings of mine; that's what struck me; she didn't ask me to submit something for them to consider. So I said yes, and then she brought me on for a string of exhibitions in Italy, and one in London, a kind of tour. Early on we added the other two paintings in the series -- we called it "Sonoran Lace, Seasonal Moods - Landscapes at the Borderline" -- and we made a big, four-piece splash of color on the walls of those exhibitions. Maybe that helped too. And I want to thank Maria Teresa, along with ITSLIQUID, for believing in me and being so helpful. My agency in New York has since produced a small Artist Edition series of full-size prints, and they are negotiating a sales contract for the first set, the #1s out of 5, as well as the four originals. So, yes, the gatekeepers in Europe have done me a great service by their interest in my artwork, and their praise of it. We must remember, however, that in America it's all about money. You're nothing till your value goes up. Maybe that has something to do with it too.

Your background as an author and poet offers a rich tapestry of narrative and linguistic insight. How does your literary prowess intersect with your visual art practice? Can you illustrate how storytelling techniques from your writing inform your visual compositions, or how visual elements inspire your literary creations?

My writing background, mostly fiction and journalism, have certainly impacted my painting in that the same uses of example and obscure motive enter my paintings that propelled my written storytelling. But after years of writing fiction, reading fiction, rewriting fiction, my interest in the realism of most literature began to wane. I was almost exhausted by it. I longed for a chance to peel away from it. First, I found help through poetry but even that always seemed necessarily tied to the literal current of life and too confining. I wanted something even more magical. As Faulkner once said: All novelists are failed short story writers and all short story writers are failed poets. To simplify is golden. I would add to that: Many poets are failed painters. They desire in their souls to leap out of the strictures of the written word and into an artform that more directly strikes at the heart of the viewer (reader) in a big, simple, straightforward way ... all you have to do to enjoy it is open your eyes ... and so I tried that. I returned to that, in a way. Picasso proclaimed that all children were artists. And to do it, without even realizing it at the time, I returned to the ways of my childhood, when, whatever natural gifts you possess, your perspective on life was completely free and true. You dream of building things and rely on first impressions, the best ones -- that immediacy! -- to make your feeble appeal. I still feel that joy at times ... making art only for the fun of it and because for some reason you seem to be good at it, good enough and willing enough always to try new things. It becomes play! You can feel it in the same way a young baseball player feels it when he is playing in a game. An earthy thrill. It's a serious, magical gift to be able to pass your life playing around and using your hands, building things. I'm as much a childish carpenter, a builder of toy houses, as I am an artist. Being called a Global Virtuoso is one thing, but I would call myself first an American folk artist ... self-motivated, self-trained, self-promoted, self-financed, self-indulgent, self-secure. And I apparently never grew up.

The central question in much of my art is: Who knows the ways of the human heart? This is often the responsibility of the title, to point the way to a human story even in works that originated in pure abstraction. It helps me often see the narrative possibility in something that started out with no theme, no intention but to depict a scene, a landscape, even a portrait, or to simply paint a collection of emotions into a synthetic whole of oil paint or watercolor or whatever. All great art has a beginning and an ending; it's just a matter of where you start and where you end that concerns the artist. He must reach out and claim his territory, every corner of it. Even Rothko, in his brilliant purity as an abstractionist, went so far as to paint in the boundaries of his artworks, as if to say: you must focus here to see the magic. If a painting lacks these qualities, a beginning and an ending, no matter how obscure -- a whole that is captured within the framing of the work -- it risks becoming little more than wallpaper. This year, with the encouragement of a singular friend, I returned to the land of the living after several years of wandering through my desires and necessities, looking for a new signature, a new style almost, an approach to my work that is more cohesive and recognizable as mine. And then one afternoon it all came together. You need only take a close look at the PORTFOLIO page on my website to see it. For one thing, I've gone to larger canvases. I'm now painting memories of stories from my life, events, people, situations -- even trying to recreate the view of a memory by incorporating elements of abstraction to what is otherwise a complete embrace of expressive representationalism, as you might call it -- and it all has one singular element in its thematic construction. The core of it all is how we rose from the Earth and how we shall return to the Earth, Rust unto Gold. Everything in between is the human part, your one precious lifetime. The marvelous Southern writer Flannery O'Connor boiled human life down to two elements: mystery and manners. The best art reflects these properties.

Having experience as a book critic and literary magazine editor, how do you approach the critique of your own artwork? Do you seek feedback from peers within the art community, and how do you integrate constructive criticism into your creative process while maintaining your artistic vision?

I am pretty much a hermit, and I work (almost) every day, especially these days with all this new attention. Lately, I spend more time writing and receiving emails -- and updating my website -- than I do at the canvas. Let me mention that I've only been to two museums in the past ten years, and no galleries, no shows, no exhibitions. I know, on a personal level, only one artist; she is first a poet and writer here in Texas and my best friend. Painting is her backup, you might say, and she's a day's drive from me. She's never commented on my work but to encourage me in the next one, and she owns a number of my paintings. I have an online friend -- we've never met in person -- the magnificent sculptor Terrence P. Fedde, out of Tulsa, Oklahoma -- and he has over the years pointed out to me several of my works that he appreciates, using a positive form of constructive criticism, I suppose, and he made the suggestion that I produce a self-portrait based on a particular photograph. I had posted the photo on Facebook as something of a joke, taking on the role of a tough guy, showing off my fists and the like. Terrence commented: "Who's going to paint it?" After a year or so of holding it in the back of my mind, I took up his challenge. It became "An Irishman in Texas," and we now have a collector interested in buying it. In fact, no one has ever offered me any constructive criticism, and since it's difficult for me to take to heart even my own criticism, as every painting demands its own drama and execution, and each one is a new effort to expand my capabilities, and since "feedback" doesn't matter, as in I don't want to paint like anybody else, it's useless to me. Indeed, one reason I live in this kind of isolation is to avoid other artists and the intelligentsia and to evade the temptation to alter my work based on the opinions and styles of others, much less the advice of others.

My formal education in making art is quite limited. I took an art history class in college, and I've taken four art courses in my time, and that was almost thirty years ago ... three drawing classes and a watercolor course. It was at a small college in Champaign, Illinois, but in my mind I was already better than the professors so I stopped going. All I've ever heard is praise anyway, whether I deserved it or not. Once in a while an acquaintance or a service person will say something that influences me. Not long ago, my neighbor came in to see me while I was working and she blurted out: "Stop, don't do any more!" Though I had imagined several more days of detail work, the next morning I touched off a few things and signed the canvas. I've been using the same basic pallet ever since. Sometimes, online, Facebook or Instagram, someone will say something crude but I consider such comments to be little more than heckling, and I often reply with a crude comment. For myself, if I put my moniker on the canvas and post it to my website, then I approve; it's time to abandon the project for a new one; it's time to move on and do better the next time. I'd frankly love to hear some constructive criticism. I'm always curious to know how viewers react to my work. Once a lady said of an abstract work that her "seven year old could have done that." My response: "So could I!" And I truly wish now that I had started my art practice at about that age instead of waiting so long. My one big regret!

Your works often delve into themes involving people and landscapes. How do you philosophically approach the depiction of the human experience in your art? Are there particular human conditions, emotions, or existential inquiries that you find yourself repeatedly drawn to exploring through your visual medium?

The Man Woman Question, a topic I first encountered in a meaningful way in a college course on basic philosophical topics, and which has changed dramatically in my lifetime with the feminist movement, remains perhaps the most compelling condition that interests me, and I have returned to it recently with a couple of new paintings, "Roadhouse Honeymoon" and "Crawling Back Again." I've always tried to paint strong women, who, even in the nude, convey a sense of power over their lives and the ability to master the challenges they face. I've never painted women as only beautiful objects couched in simple scenes of wildflowers and puppies, or even as sex objects lounging on a bed wrapped in the bed sheets while receiving a bouquet of flowers from her client via the hand of a maid. Prostitution is a perfectly honorable line of business but for its many dangers, and its low social esteem in a prudish world. The dangers of religion and ignorance, given their history of ripping up societal fabrics all over the planet, also interest me. We too often are led by lies, and too often do we follow. Otherwise, especially in my abstracts, it's the glory of the natural world that fascinates me and trying to grasp in a painting its spirit and energy is the only question.

Your recent accolades, such as the Future of Art Global Masterpiece Award, suggest a significant impact on the future of art. What is your philosophical outlook on the evolution of art in the contemporary era? How do you envision your own art developing in response to the rapidly changing sociopolitical, environmental, and technological landscapes of our world?

Frankly, I strive to avoid such huge topics in my work, preferring to focus more on a character's concrete, earthbound, day-to-day struggles. If those struggles are illustrative of a larger conundrum of some sort that the world is concerned about, then so be it, but I never start out saying to myself that I want to paint a picture that illustrates a certain sociopolitical, or environmental or technological issue. Still, though, I have touched at times on various theological dilemmas and the often absurd influence that mysticism and religion and tribalism in general still pose in a time when we have learned so much about how the Earth was put together and how life itself truly evolved. Art will survive, and evolve into no telling what, no matter what particular epoch it is associated with or whatever it is called. What is this epoch called, anyway, besides Contemporary? Shall we always be known as The Contemporaries? The truest art supersedes periods, or movements, or epochs, or trends, or popularity, or methods, or eras, or the shuns of purists, or even failure in the long run. The art that survives is work that reaches into the viewer's heart and grabs it by its ears and then screams into its face that all of human life is ultimately, as Einstein confirmed, a function of the imagination; knowledge, skill, talent, these are but the tools of the imagination. In the end, all art that lives through the machinations wrought upon it by the intellectual gatekeepers and by popular sentiment and by the hazards of history shall remain Contemporary. It's a pretty good title.

"Catherine's World (Rust unto Gold)," mixed on canvas, 40x60 in, 2024

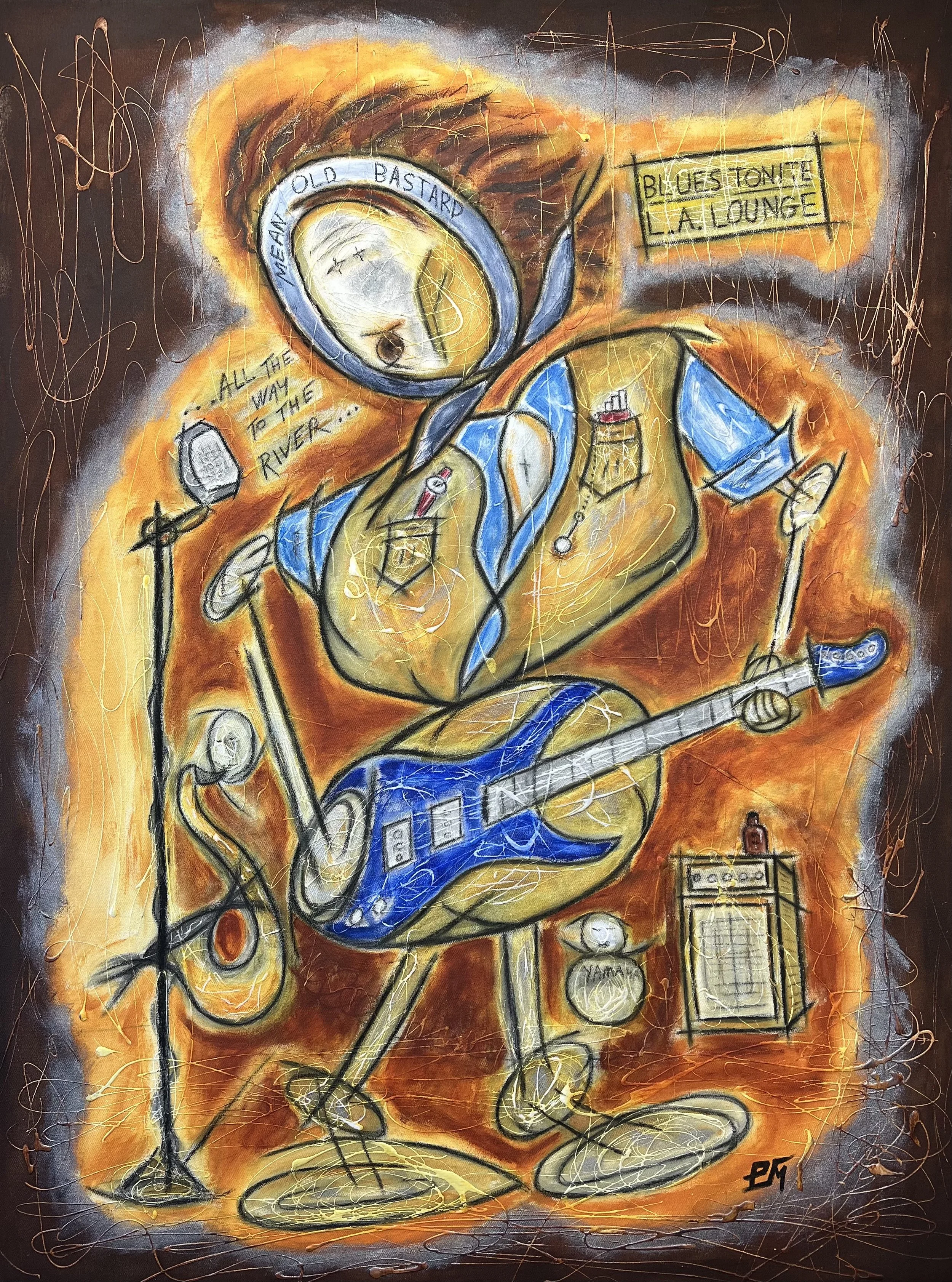

"Master of Disaster (Rust unto Gold)," mixed on canvas, 48x36 in, 2024

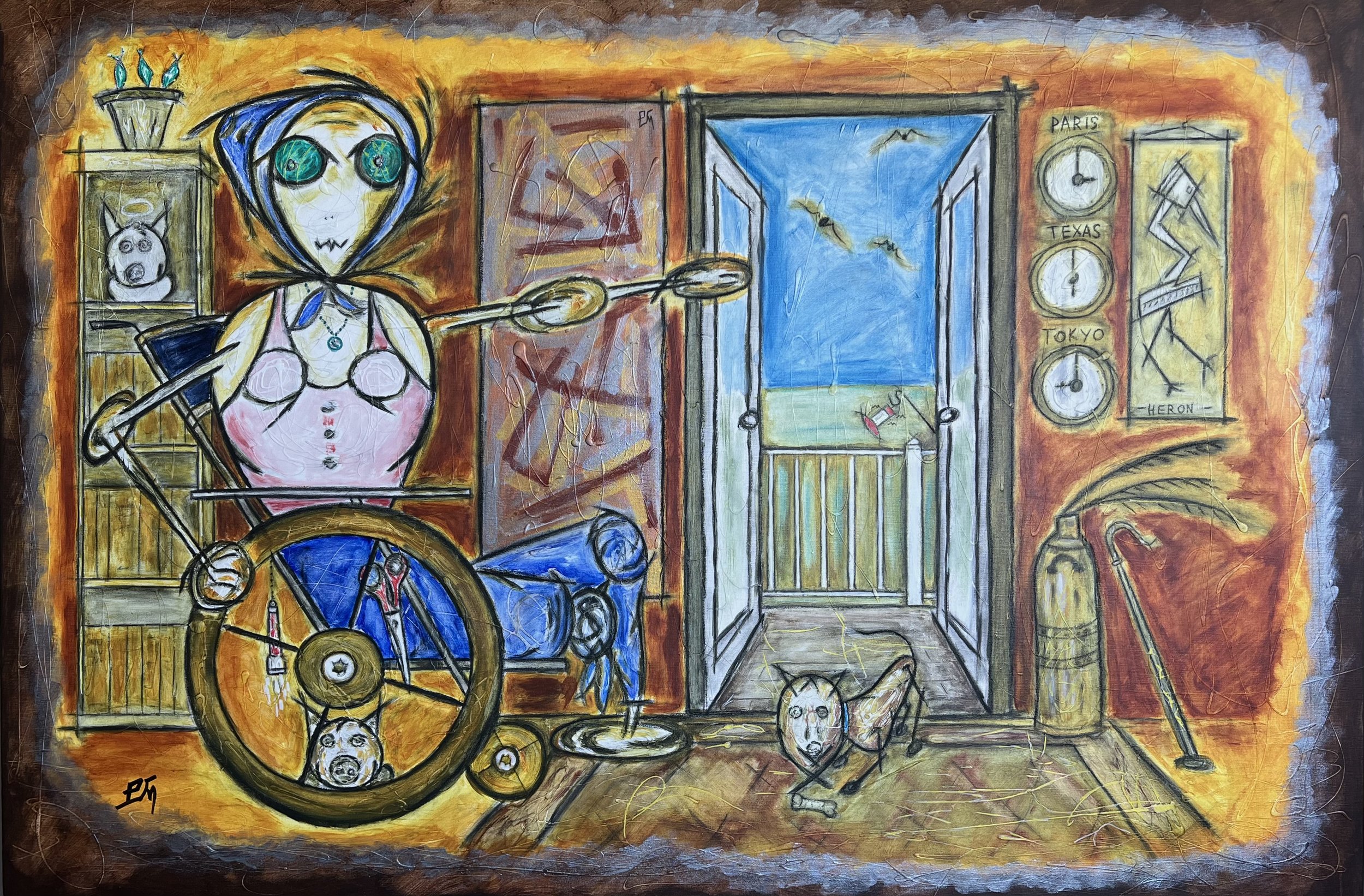

"Crawling Back Again (Rust unto Gold)," mixed on canvas, 48x36 in, 2024

"Roadhouse Honeymoon (Rust unto Gold)," mixed on canvas, 36x60 in, 2024

"Weeping Boy (Rust unto Gold)," mixed on canvas, 48x36 in, 2024

"Gaza - 3rd of May (Rust unto Gold)," mixed on canvas, 36x60 in, 2024

"The Suffering of Leonardo (Rust unto Gold)," mixed on canvas, 48x48 in, 2024

"Mother and Child (Rust unto Gold)," mixed on canvas, 48x48 in, 2024

"Savage Embrace (Red #4)," mixed on canvas, 63x32 in, 2023-13

"The Shattered Spine," acrylic on canvas, 48x24 in, 2020

"Bare Limbs, Bradley's Old Place (Aftermath)," acrylic on canvas, 40x30 in, 2019

"The Mountain Cat and the Missionary (Storm #1)," oil on canvas, 32x54 in, 2011

"Sonoran Lace #4, Winter," oil on canvas, 56x32 in, 2009

"Dark Matter #2," oil on canvas, 48x36, 2004

"Searching for the Treasures of the Earth," oil on canvas, 48x36 in, 1999